A Jonathan Richman Primer

Dissecting The Power Pop Wunderkind's Deep Catalog

Less than a page into Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, Will Hermes’ definitive book on the intersecting music scenes of 1970s New York City, someone rips their shirt off. But context is key—the culprit was a 21-year-old Jonathan Richman, who shaped the self-aware sex symbol role like none other before him. He started performing his own songs 5 years prior in the Cambridge Commons, either frightening or enticing passing intellectuals by projecting his voice and his unfiltered perception.

He’s always sang what he sees, banking on charisma, a couple chords and a “first thought, best thought” mentality to elevate earnest rock songs. “Cappuccino Bar” expresses the anxiety of overcaffeination. On “You Can’t Talk To The Dude,” Richman empathizes with an awkward roommate situation. With hits like the Velvet Underground-inspired “Road Runner,” he claims to have never wrote down the words.

Richman never lost touch with lyrical genuity, regardless of which iteration he was playing as: the Modern Lovers, Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, or Jonathan Richman, solo. The original Modern Lovers released their self-titled debut post-breakup in 1976, before Richman trekked out west and formed a new lineup. That configuration was short lived too, though. These days, he’s solo full-time, save for regular live collaborations with drummer Tommy Larkins. Later this month, he’ll be warming up FYF Fest’s very stacked Saturday lineup with one of the earliest slots of the day, and it’s well worth braving the heat to catch his signature guitar strap-less jaunt. Amid a fairly massive discography, we picked five of his best introductory records to set the mood.

The Modern Lovers (1976)

Recorded intermittently beginning in 1971, this compilation of recordings from the original Modern Lovers lineup is technically the first album of Richman’s ouvere. He hardly acknowledges it as such, though. The Modern Lovers captures the starry-eyed vision of teenage Richman, armed with a Jazzmaster in a public park. At 20 years old, he was still straddling different sounds, undecided on the tone of his own. The Modern Lovers—the 1976 album he considers to be his real debut—showcases the jangly, harmony-heavy style that he eventually settled into. Thankfully, he never departed from the wholesome poetic vision driving The Modern Lovers.

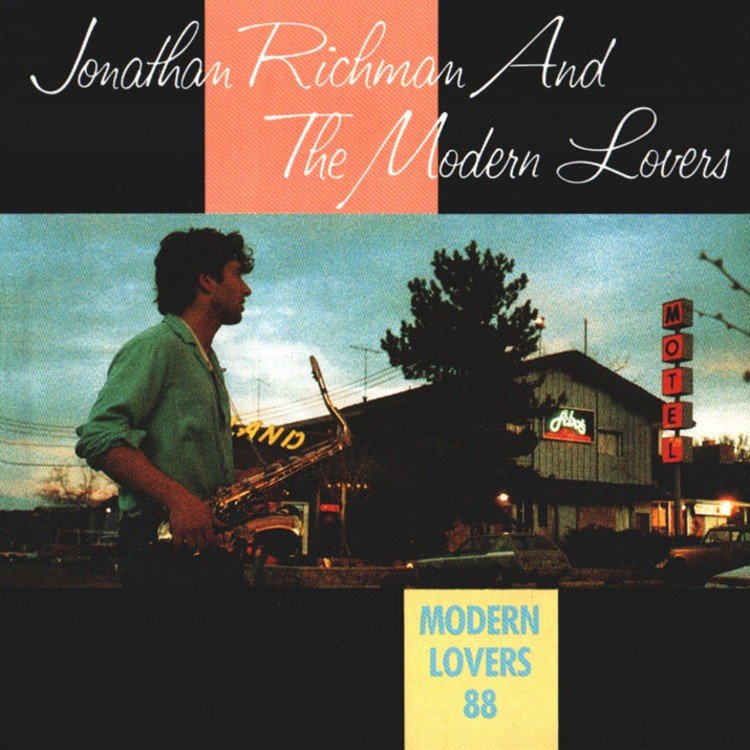

Modern Lovers 88 (1988)

Richman’s second incarnation of the Modern Lovers (innovatively named Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers) featured an evolving lineup over its 12-year run. Modern Lovers 88 marked their final release, topping off the Modern Lovers project once and for all. Here, Richman’s decade-plus spent tinkering with his backing band pays off in full choral force. With a total of four words and one twangy, acoustic solo, “Gail Loves Me” elevates indistinct vocal lines over Richman’s typical observational poetics. He’s showing off his final pack of Lovers, and with pitch like that, who can blame him? Modern Lovers 88 is the album of the summer every year, a love letter to the season spent outdoors, sleeveless. To refrain from singing along would be a summertime sin.

Having a Party with Jonathan Richman (1991)

Finally freed of the Modern Lovers moniker, Richman kicked off the ’90s with the mildly confusing Jonathan Goes Country. His rockabilly riffs live on, but the record leaves a gaping hole where his sense of humor should be—that’s where Having a Party with Jonathan Richman picks up. Tempo shifts and vocal asides á la Exile on Main St. (a “woo!” here, a “yeah!” there) make Richman’s sassy self-criticisms all the more danceable. A few songs including “When I Say Wife” are recorded in front of a live audience, featuring some well-timed spurts of laughter and following applause, loudest when he croons, “Wife sounds like laundry.” His speak-singing tendencies go full monologue on “1963” and “Monologue About Bermuda,” reminding us that his talents have always transcended songwriting. He’s a storyteller at heart.

I, Jonathan (1992)

More than any other Richman record, I, Jonathan maps his trajectory since the Modern Lovers’ 1976 debut. It takes him less than 45 minutes to touch upon all of his trademarks: hand claps, close harmonies, near-nursery rhymes about skydiving or the magic of Lou Reed. He exhibits that characteristic childlike enthusiasm without coming across as naive. Instead, his elation unveils an appreciation for the most underrated pleasures—nice weather or your favorite song by your favorite band. “I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar” reveals his passion for the unknown, what he hasn’t seen or felt before. But on “Twilight in Boston,” strolling through the suburbs, he sees the charm in familiarity, too.

You can buy the VMP edition of this album right here.

Not So Much to Be Loved As to Love (2004)

It’s difficult to imagine loving love as much as Richman does. He released Not So Much to Be Loved As to Love less than a year after tying the knot, resulting in record-breaking levels of romance. After nearly three decades, sticking a hook in a serenade still yields sweetness. Even the instrumental “Sunday Afternoon” sounds like Richman in every right, substituting for lyrics with the equally intimate cuddling of guitar and bass. This past Valentine’s Day, Richman opened for Angel Olsen at the largest headlining show she’d ever played. He included one of the catchier cuts from Not So Much, “My Baby Love Love Loves Me Now”—a true tale of appreciation. At his core, Richman accepts love more readily than most. That’s probably the most childlike quality he possesses. Every time sounds like the first time.

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!