The musical world around vinyl has changed beyond recognition in 20 years and, with it, the reasons for people buying it. What keeps it going?

For my sins, I am 41. Born in 1980, there are niche but keenly contested arguments as to whether I’m a tail-end Gen X, early Millennial or part of a cohort that doesn’t belong to either larger group. I start this piece with this information so that you may contextualie my efforts to talk about people rather younger than myself with the appropriate amount of patience, condescension or derision; the choice is yours. In an effort to minimize the latter, I will be limiting myself to talking about vinyl.

Even viewed through this narrow focus, though, the world has changed beyond recognition. The landscape of consumer music has changed so enormously over the course of this century as to be unrecognizable. The means by which we consume music, the formats it is available in and the hardware we use to access it (when we use dedicated hardware at all) is radically and invigoratingly different to what was once the norm. In amongst this, vinyl persists; a cosmological constant in a world of variables. It is such an outlier, it is only logical to take a step back and ask: Why?

While vinyl’s popularity has been consistent, the motivations behind owning it have changed, too. When I bought my first turntable in 2001, it served a very specific purpose. Music released before 1992 was available in amounts that would be unfathomable now and it was dirt cheap. In a world with no on-demand streaming of any description and the major labels ensuring their margins on CD were very healthy indeed, vinyl was a cost-effective means of accessing older material. In 2001, the idea of buying new records barely even crossed my mind. Vinyl had a role to play and it did it very effectively, but it supported CDs rather than replaced them.

This is because CDs were omnipresent. By the turn of the century, the process by how it might be replaced was available in an embryonic form, but you could reasonably argue that neither the quality nor the convenience aspect of that had been achieved yet. The manner in which CD represented the dovetailing of both of these elements is something that streaming has only just surpassed. It worked in your car but the same disc could then be used at home with superb results (and I use ‘superb’ without irony; as much as I love records, I’m not above saying that a truly well-mastered CD can still astound). It was absolutely logical that the starter audio system of 2001 was CD-fronted.

What is important to mention before we compare and contrast to the present day is that there has been an intervening step that “true” Millennials will have experienced more directly. Halfway through our 20-year snapshot, the state of play had some things in common with 2001 and others more akin to now. New vinyl was a much bigger part of the pull of getting into analog, and a priceless advantage that we enjoyed by this point was being able to use streaming to decide whether it was worth paying out for the record before we did so.

Streaming (and before it, the iTunes and torrenting boom) changed the quality angle that many people had with vinyl quite considerably — and as someone who has been working in the audio industry before, during and after the early period of streaming and now into the present, it has created a fascinating anomaly. There is a group of people across the world whose formative relationship with audio (and video, and indeed, to an extent, the wider internet) occurred in a period of unique restriction. They had access to vast swathes of music but in compressed form and frequently via data contracts that wouldn’t stand up to significant use on the move. Get too ambitious with storing content offline and the limited storage capacity of the time quickly became an issue, too.

For this subset of people, many of whom might be seen as “peak Millennial,” vinyl was the high-quality medium of interest. They had little interest or affection for CD as a format and while digital was an important component in their listening, it was one that fed the convenience rather than outright performance angle. Records were increasingly widely available again and even fairly basic setups would trounce Spotify. The people in this cohort differ in outlook, listening practices and frequently in the equipment they own to both the generation before (of which, in this instance, I include myself as part of) and the generation after.

This difference is arguably more pronounced with regard to Gen Z because, while I predate compressed digital, it still formed a huge part of my listening for many years. My dealings with Gen Z bring me into contact with a group of people intensely relaxed about quality. And why not? We have now retuned to a situation where the most convenient option — on-demand streaming — is once again also an exceptionally high-quality option, too, supported by download speeds, data caps and storage capacity of enormously greater capability. It’s hard to overstate this quality angle either. By odd coincidence, the first piece of digital home audio equipment capable of playing 24/96kHz digital material made its debut in 1996 (generally considered to be the first year of births for Gen Z) at a cost of $12,000. Fast forward to the present, and significant chunks of Apple Music are available in this resolution or higher for $10 a month. There has never been a democratisation of quality in audio like it.

So, in a world where you can listen to pretty much anything you want in superb digital quality, why does vinyl persist? More pertinently, why is it winning over a section of Gen Z listeners, too? The relationship new arrivals have to vinyl is by necessity different to the one that I had; there are moderately uncomfortable parallels to the housing market in that myself and my contemporaries hoovered up those interesting old records at a great price many years ago and have no intention of selling up. There are still bargains to be had, but they are rather harder to eke out than they once were. The logical bargain argument of vinyl is as restricted as the argument over how analog represents the best possible quality.

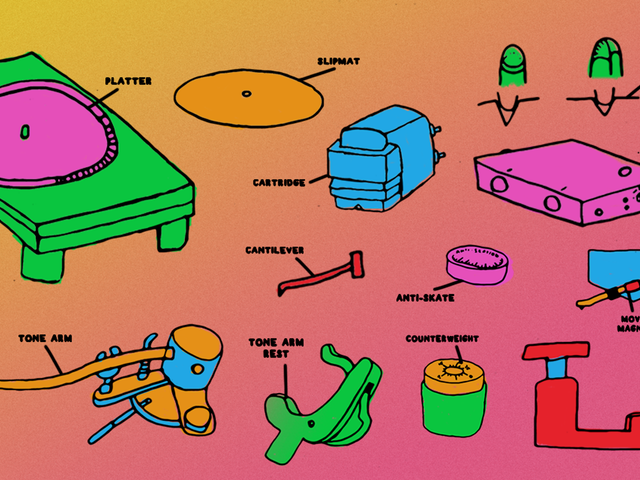

Some of the ongoing appeal can be chalked up to the nature of how we relate to records and record players. Many years ago, a younger and less divorced me wrote about this very phenomenon and the fundamental satisfaction of vinyl as a medium to use still plays a role in decisions people make as to whether they want to get on board. There’s also a more prosaic appeal based around how vinyl is quite free from the normal rules of depreciation and obsolescence. Most other things we own now have finite lifespans and lose their value at something between a graceful arc and vertical plummet, and the absence of this in vinyl is intensely gratifying.

I think that the main pull is now the records themselves, though. Vinyl has always been a beautiful medium but with more focus back on new material, the aesthetic of records themselves has never been more developed than it is now (this is, by the by, also behind the return of cassette; a format I grew up with and find the resurgence of both charming and largely incomprehensible). Without compromising on the performance that can be extracted from it, vinyl has partially evolved into a new role of being both a delivery and an artistic medium. In a contest between buying a record collection and an NFT of a depressed looking monkey, which might be worth a fortune or potentially the same as any other jpeg on your hard drive, the records win out more often than not.

Combined with some of the truly beautiful hardware available, the result is usable art; something that delivers at a few different sensory levels at once. I can make cogent and sober arguments that the sonic performance of my latest turntable is justification alone for me having spent a sum of money I’m going to plead the fifth on to secure it, but there’s no arguing that I don’t tend to happily watch my digital front end work in the same way. Does this mean that, in its latest evolution of “usable art,” vinyl has cracked the secret to staying relevant regardless of what the digital sphere does? Maybe, maybe not. But the fact that it has managed to win over successive generations who agree on precious little else, against an ever-changing backdrop, means you shouldn’t bet against it.

Ed is a UK based journalist and consultant in the HiFi industry. He has an unhealthy obsession with nineties electronica and is skilled at removing plastic toys from speakers.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!