Donald Byrd Was The Future

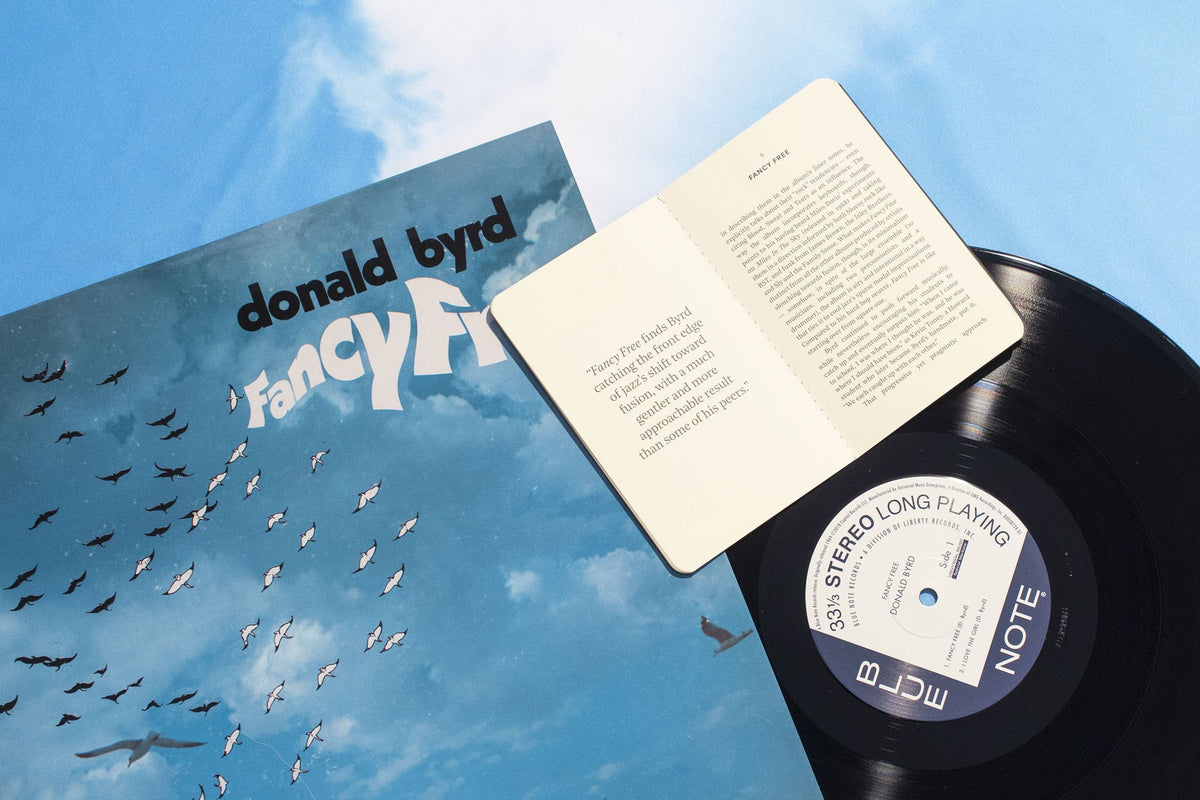

Read An Excerpt From Our Liner Notes For Donald Byrd’s ‘Fancy Free’

In October, members of Vinyl Me, Please Classics will receive Fancy Free, a 1970 album from Donald Byrd. Originally released on Blue Note records, and just a few months after Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way, it’s a seminal album in the fusion between electronic music, funk and jazz. Read more about why we picked this title over here. You can sign up here.

Below, you can read an excerpt from our exclusive Listening Notes Booklet that is included with our edition of Fancy Free.

“It is relaxed, isn’t it?” Donald Byrd asked Nat Hentoff — author of the original liner notes to Fancy Free — of its title track. The 12-minute meditation has a breezy, almost beachy quality that, looking back, marks a sea change in Byrd’s discography. Yes, it’s the album where Byrd went electric thanks to round, warm keyboards from Duke Pearson — but the gap between the release and his preceding projects is more substantial than the fact that recording it required an additional outlet or two.

In the late 1960s, the by then well-established Byrd was entrenched in brash, soulful, swinging hard bop; on Slow Drag and The Creeper (both recorded in 1967 for Blue Note), he performed it virtuosically. But Fancy Free finds him catching the front edge of jazz’s shift toward fusion, with a much gentler and more approachable result than some of his peers produced. Its innovations lie in its source material: Fancy Free adapts the vernacular of funk and R&B more than it does that of rock, the inspiration for most jazz fusion records that are considered canon. Hindsight so often being 20/20, Byrd’s take on fusion — work that was then greeted skeptically — is looking more and more prescient. “I’m not trying to be avant-garde or a hippie,” the then 37-year-old Byrd explained. “I’m me, and a lot of different things interest me at different times. And since I’m not pressing to be something other than myself, the sessions come out as relaxed as I can make them. As this one did.”

His demurring approach to invention was, perhaps, a result of his ability to challenge institutions while functioning quite deftly within them. What the Detroit native is best known for in the jazz world — where the post-Fancy fusion recordings that eventually earned him his greatest success (and immortality via hip-hop sampling) are looked upon with some derision — is his devotion to education.

Specifically, Byrd had a lifelong fascination with helping higher education better serve black culture — not necessarily by codifying it, but by placing it within its own intellectual tradition. “We are trying to discover what is black in this music,” he told the Washington Post shortly after becoming the founding director of Howard University’s jazz studies program in 1968, the first of its kind at a historically black college or university.

Byrd, born Donaldson Toussaint L'Ouverture Byrd II, thrived in academia. He earned a Bachelor’s of Music from Wayne State University while playing in Air Force bands, which eventually took him to New York. There, he got a taste of performing alongside artists like Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, and eventually enrolled in the Manhattan School of Music to earn his master’s degree.

Though he began recording for Savoy and Prestige as a bandleader — while tackling absurd numbers of gigs as a sideman, including 29 sessions in 1956 alone — almost immediately after arriving in the city, his commitment to education never wavered: He taught music at the Bronx’s Alexander Burger Junior High School, not far from the apartment he shared with a young Herbie Hancock in the late 1950s (the street where they lived is now named for Byrd). In 1963, he traveled to Paris to study with famed compositional pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Byrd eventually accrued two more master’s degrees (from Columbia University), a law degree (from Howard), and his doctorate (from Columbia’s Teachers College). He preferred to be called Dr. Donald Byrd.

As literally by the book as Byrd’s trajectory might seem, his arrival at Howard in 1968 was as a revolutionary — not as an ivory tower-bred insider. It was a role he took pride in: When explaining the man he was named after, Haitian revolutionary martyr Toussaint L’Ouverture, he noted that “the idea of a namesake is to remind you what you're supposed to be about.” Byrd’s hiring was prompted by the 1968 student sit-ins at Howard, which in part were a protest of the perceived disconnect between the university’s curriculum and black history and culture. At that time, jazz, blues and gospel performances were not allowed in the fine arts building, and students could be expelled for using practice rooms to work on any non-Western classical music.

So Byrd was brought in as a peace offering during negotiations spurred by the protests — a teacher tasked with starting not only the school’s first jazz band, but also jazz history courses and seminars. “At all these schools where he taught, he had a problem with the administration because of his approach to teaching,” fellow Detroit trumpet player Marcus Belgrave said later. “Because they didn't have respect for jazz.” What Byrd quickly realized though was that, administrative issues aside, his role as a mentor was just one more way of continuing his education. “I was greatly influenced by the students [at Howard],” Byrd said in a 1976 radio interview, by way of explanation for the fusion records that had, by that point, brought him great mainstream success. “We taught each other — we moved each other in that direction.”

Fancy Free, recorded the spring after his first year teaching at Howard, was Byrd’s recorded debut as a genre agnostic. Just four songs (three other tracks, which included vocalists, were rejected by the label), the album balances bombastic improvisatory momentum with an impeccable sense of atmosphere and feel. The self-titled opening track is a bossa nova-inflected groove written by Byrd; the second track, “I Love the Girl,” is a stripped-down, heartfelt ballad that he says was inspired by Barbra Streisand — as in her music, not her person. The latter two tracks were both composed by Byrd’s students; Charles Hendricks, author of “Weasil,” was then under his tutelage at Howard.

Unsurprisingly, those are the two tracks that feel the most tethered to Byrd’s earlier work; yet, in describing them in the album’s liner notes, he explicitly talks about their “rock” tendencies — even citing Blood, Sweat and Tears as an influence. The way the album incorporates keyboards, though, points to his having heard Miles Davis’ experiments on Miles In The Sky (released in 1968) and taking them in a direction informed by both bluesy rock like BST, and funk from James Brown, the Isley Brothers, and Sly and the Family Stone. What makes Fancy Free distinct from all the other albums produced by artists slouching toward fusion, though, is its minimalism — somehow, in spite of the large ensemble (10 musicians, including two percussionists and a drummer), the album is airy and intentional in a way that ties it to cool jazz’s sparse modal improvisations. Compared to his hard bop oeuvre, Fancy Free is like starting over from square one.

Byrd continued to push forward musically, while nevertheless encouraging his students to catch up and eventually surpass him. “When I came to school, I was where I thought he was, and he was where I should have been,” as Kevin Toney, a Howard student who later became Byrd’s bandmate, put it. “We each caught up with each other.”

Byrd always embraced sampling, which was a good thing for hip-hop since his music grounded a number of the genre’s most beloved beats. “Weasil” was sampled by Lords of the Underground and Hard Knocks, but mostly Fancy Free signaled a shift toward the commercial viability that would make Byrd’s later records so familiar and evocative to hip-hop producers. His ability to connect with and collaborate with younger musicians, combined with his willingness to play music that the jazz establishment (of which, ironically, he should have been considered a standard-bearer) deemed corrupt, helped him completely reinvent his career. Within a few years, Byrd went from downtown jam sessions to rock festival stages.

After Fancy Free, Byrd’s recorded experiments with fusion continued; at Howard, he taught producers Larry and Alphonso Mizell, who eventually helped design the series of groovy yet timeless 1970s albums that made Byrd a household name. Their first collaboration, Black Byrd (1973), went platinum and lives on in Nas’ “N.Y. State of Mind” and Public Enemy’s “Fear of a Black Planet.” But most importantly, Byrd re-established a contemporary musical connection between jazz and the people he’d devoted his life to teaching: the youth, and specifically young black people (he would go on to establish jazz programs at two more HBCUs over the course of his career). Jazz didn’t need to be a relic, taught like ancient history. Instead, it could be a living art — a part of black culture as connected to academia as it was to the streets, as Byrd once described his own music.

What set Byrd apart from the jazzers who called him a sellout — on Fancy Free, and after — was a willingness to use his intellectual curiosity to dive into what was coming next, instead of to continuously relitigate the past. Why was he as interested in hip-hop as he was R&B, rock and funk? As he put it during a 1994 appearance on the TV show Rap City, “I knew that something new was getting ready to jump off.”

Natalie Weiner is a writer living in Dallas. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Billboard, Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, NPR and more.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $36Pages