Arkansas Record & CD Exchange Is The Best Record Store In Arkansas

The 50 Best Record Stores In America is an essay series where we attempt to find the best record store in every state. These aren’t necessarily the record stores with the best prices or the deepest selection; you can use Yelp for that. Each record store featured has a story that goes beyond what’s on its shelves; these stores have history, foster a sense of community and mean something to the people who frequent them.

It’s said that the earliest settlers in Arkansas were the crazies, the criminals, and the charlatans looking for a new haven to protect themselves from foreign ideas, foreign invaders, and to take advantage of virgin opportunities to plunder the land and native people of their riches. Hernando de Soto died here doing that very thing. He convinced the Quapaw Indians he was a deity, and when he didn’t find anything of value and the Quapaw weren’t buying his line of shit, he ordered the massacre of their men, women, and children from his deathbed just for the hell of it. To further keep up his con about his immortal coil, he was weighted and sunk in the Mississippi River to ensure a grave was not found. Add slavery, poor people living under the control of rich landowners, fly by night preachers and religious cults, and… Arkansas really didn’t stand a chance.

But despite the immortal curse of the Quapaw and the poverty, the very things that oppress the population are likely to produce a deep well within that can fuel lasting artistry. Arkansas has produced more than its fair share of iconic musicians, but they often have to leave the state, to a place where they’re no longer constantly under the control of the bossman, church, or body politic.

The first rule of being a musician in Arkansas is get out of Arkansas. The credo to exit Arkansas in search of oxygen for the muse was wisely followed by a whole bevy of musicians you might not even be aware started their lives in Arkansas. Famous L.A. session guitarist and Arkansan Louis Shelton (he played some of the most memorable guitar parts for The Monkees, Jackson 5, and Lionel Richie, to name a few) once told me that in the late 1950s he followed his friend Glen Campbell out of the state to work in the mines of New Mexico as a path to a career in music. That’s right. Mining in New Mexico was better than living in Arkansas and trying to make a career out of it. Sister Rosetta Tharpe followed the tent revival circuit out of town and, like so many other black southern artists, landed in the more hospitable environs of Chicago, where music was valued and consumed at a level that made survival as an artist possible. Beth Ditto and Nathan Howdeshell fled the duopoly of the rivaling religious shame cults of Pentecostals and the Church of Christ for Olympia, Washington, to be free to express themselves and find like-minded co-conspirators to form Gossip in the late ’90s.

Needless to say, Arkansas has not progressed so much that anyone is going to challenge it for the (insert genre) Music Capital of the World. Though, when you consider our musical icons: Johnny Cash, Sister Rosetta, Levon Helm, Louis Jordan, Charlie Rich, Sonny Boy Williamson, Al Green, Pharaoh Sanders, and the list goes on… it should be considered a mecca for music fans. But the native population’s scarce support for local heroes dovetails with its general ambivalence toward musical culture in general. I have seen Shuggie Otis play a once-in-a-lifetime show in Little Rock to fewer than 25 people. I have seen Roseanne Cash playing an acoustic show in a small club, while some goober thought it might be OK to play along on harmonica from his seat in the audience. I’ve seen Levon Helm in his later years play in a parking lot with a cover band to almost no one. So, it’s left to the true believers and the clandestine who have to support each other and find sanctuary where they can. In Arkansas, one such sanctuary is Arkansas Record & CD Exchange.

Arkansas Record & CD Exchange is located in the most unlikely of places — in a neighborhood called Levy, in the midst of a strip mall in the deadest of dead neighborhoods in North Little Rock, Arkansas. It’s dead, not in that it’s crime-ridden and scary to the uninitiated, but dead in the sense that it appears as though it’s an island whose only bridge to the mainland washed out in the 1980s and everyone and everything was left behind and stuck in time. I’ve played in bars since before I could drive and once, in an unfortunate zoo-themed club in Levy, I was banned from ever playing there again because I refused to take my hat off inside the club, breaking one of their strictly enforced house rules. Never mind that I’m pretty sure it was a front for multiple illicit activities — rules are rules in Levy.

Arkansas Record & CD Exchange’s owner, Bill Eginton, has been holding together a storefront church of sorts for the committed, the fringe, and the souls saved by rock ’n’ roll for 35 years at this point. It’s part record store mecca, collector’s paradise, and sanctuary for those who not only need their vinyl fix but need to talk with other weary travelers who get why an Evel Knievel lunchbox and a vintage J.J. Cale album matter more than ever in the digital streaming age.

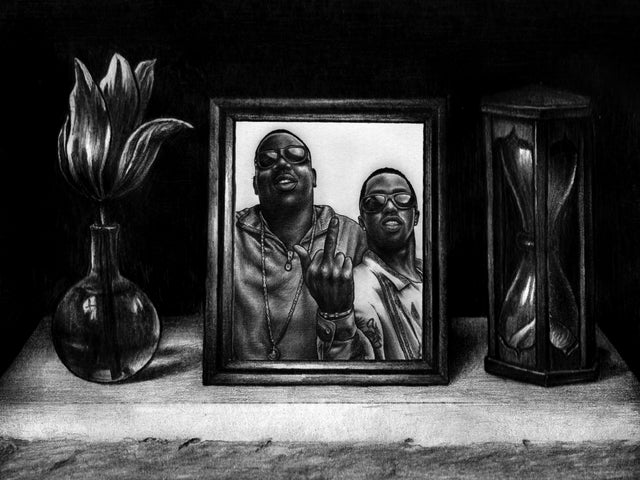

It’s hard to accurately describe the visual experience inside Arkansas Record & CD Exchange. This is not your typical metropolitan vinyl record store. In one corner, you might find a vintage kid’s record player next to a pile of vintage promo items; on a shelf you might see limited-edition box sets that are long out of print; on the walls, vintage local show posters and memorabilia, such as my personal favorite, a T-shirt from the Arkansas River Blues Fest I played in 1988 where all of the entertainers on the bill signed it and my autograph shares space on the Hanes Beefy Tee fabric with John Lee Hooker. Most famously, the store is known for its velvet rope entrance, which reminds all entering customers to remove their jackets before they’re allowed inside. It’s famous for the fact that this policy has absolutely no exception, including Eginton’s mother and Glen Danzig, who was supposedly enraged to the point of tears for not being allowed to enter without removing his leather jacket.

Eginton is a true believer. He never wanted to work in an office. He was hooked from the first record and the collecting and passion never ceased. He’s dabbled in managing some local musicians and, I’m sure, other tangential endeavors — but he’s always known that he had to find a way to be with his records and collections of other memorabilia, trains, toys, and miscellaneous detritus of the culture of his youth.

On any given day, the shop is manned by Eginton and his trusty sidekick, Reade Mitchell. Mitchell is a devotee and another true believer in the Cult of Vinyl, and is a longtime presence in Arkansas radio. He was a veteran of the 100,000 watt flame thrower, aka Magic 105. Now defunct, it was the rock ’n’ roll radio home for a generation of Arkansans. While other local DJs were hacking it out trying to be the next David Letterman or Johnny Carson, Mitchell was the Johnny Fever of this state’s WKRP. If Eginton is the preacher, then Mitchell is the deacon. Their knowledge of the canon of American recorded music is uncanny. You can’t stump them, but it’s fun trying.

Eginton is the grizzled owner and he doesn’t suffer fools, but it’s also part of the charm of the place. Mitchell seems like the opportunity to talk about and listen to music all day is a lifelong dream realized. A lot of the inventory is found, some ordered, some traded, and some just wanders in. On one recent trip I carried in a plastic tub of records I had inherited from a relative’s spring cleaning. After saving the original Conway Twitty and Don Gibson albums (along with a local ’70s album promoting a new subdivision in Hot Springs, Arkansas), I took the rest to the store, in hopes they could find it in their hearts to take them in and not force me to see them in a dumpster. After doing some shopping and finding some Porter Wagoner, Dolly Parton, Charlie Rich, and Buck Owen’s impulse buys, I asked Mitchell if they had a use for them. To my surprise, they were happy to receive a tub of vintage Uncle Dave Gardner, Jim Reeves, Sound of Acapulco and similar choices. When trying to pay, Mitchell offered that it was an even trade. Neither of us were taking away prized, rare specimens of vinyl. But, like any church worth its while, some days you’re the giver and some days you’re the receiver. If you’re lucky, you’ll find one that does both.

Greg Spradlin is a musician, writer, video maker and storyteller from Pangburn, Arkansas. He has been playing music professionally since before he could drive. He currently resides in Little Rock, AR and has a record he made with Pete Thomas and David Hidalgo that he needs to put out this year. He can also skin a buck and run a trotline, because a country boy can survive. More info here: www.gregspradlinoutfit.com

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!