So you’ve decided you like jazz. You’ve opened your ears to bebop, hard bop and more. Now with summer practically upon us, you’re ready for something with mucho calor, to leap into what Tito Puente would call “jazz with the Latin touch.” In other words, jazz that incorporates Latin American rhythms.

The development of Latin jazz over the years overlaps with the changes of jazz overall, encompassing a wide range of styles from traditional song structures to free form to fusion. Even as far back as early 20th century New Orleans, Latin American music was an important component in jazz’s development—early jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton called it the “Spanish tinge.” As jazz spread north and through the Caribbean and Latin America, musicians of all backgrounds were inspired, integrating familiar melodies and rhythms with improvisational jazz. These creations in turn inspired jazz groups in the U.S. and the popularity of big band dance music in the 1930s-’40s meant bands were constantly on the look-out for music that would bring the crowds. In-demand Latin musicians either joined existing bands or formed bands of their own. Afro-Cuban, Afro-Caribbean, mambo, salsa, charanga, boogaloo, son and bossa nova are just some of the many styles of this vibrant genre of music. And there are far too many Latin jazz greats and essentials to dive into. It’s a genre that’s ever-evolving with the works of current musicians like Pedrito Martínez and Arturo O’Farrill making their progressive mark. But these 10 albums can get you started.

Machito: Kenya

One cannot talk about Latin jazz without mentioning one of its fathers, Francisco Raúl Gutiérrez Grillo, better known as Machito. He moved to New York from Cuba, eventually forming his band the Afro-Cubans in 1940 that, with the help of musical director Mario Bauzá, were among the first to combine traditional jazz arrangements with Afro-Cuban rhythms, frequently hiring American jazz composers to arrange Cuban songs. Kenya (1958) features mostly original songs written and arranged by A.K. Salim. At first glance you might think the album is all big band glitz with a loud brass section that jumps on the exotica fad of the ’50s, but if you dig deeper you can also hear what sets Machito apart from the imitators. The tight musicianship, the complex jazz arrangements that quickly turn from high-impact to subtle soulful phrases; there is no way Kenya can be dismissed as a fad album. The album also features some stellar jazz solos from the likes of trumpeter “Doc” Cheatham (“Holiday”), alto-sax great Cannonball Adderley (“Oyeme” and “Congo Mulence”) and others.

Tito Puente: Dance Mania

Tito Puente showed an early interest in music while growing up in Spanish Harlem. After attending Juilliard, he eventually landed a gig as a percussionist in Machito’s band, the timbales being his main instrument. When he formed his own band in 1948, he took cues from the orchestras of Machito and Count Basie, combining the sophistication of big band jazz with Latin rhythms. Dance Mania (1958), his bestselling album, is absolute fire. Most of the tracks are Puente-composed originals which include various styles like mambo, son, cha-cha-cha and boleros. What stands out is how polished the performances are, and yet it never feels stifled. Puente deftly plays timbales and vibraphone; the congas, bongos, saxophones and blaring trumpets skillfully back up vocalist Santitos Colón. Highlights include the mid-tempo opener “El Cayuco” which demonstrates the musicianship of Puente’s orchestra and his skill as an arranger (the horn blasts never overpower the rhythm), the lively “Mambo Gozón,” and hot album closer “Saca Tu Mujer,” a classic.

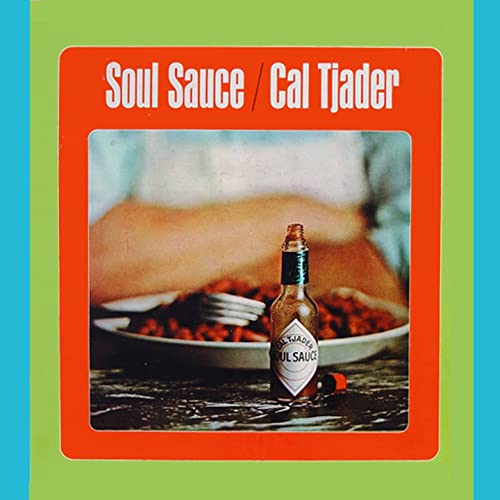

Cal Tjader: Soul Sauce

Cal Tjader, king of the vibraphone, helped popularize Latin jazz in the small group form, moving away from the big band sound. While he had no Latino heritage himself, Tjader’s discography and devotion to the idiom speaks for itself. Soul Sauce (1965) was one of his bestselling albums, a great mix of mambo, boogaloo and even some bossa nova (the João Gilberto-inspired “João”). The soulful vibes astonish with their frequent bursts, but Tjader lets his collaborators shine, too. Lonnie Hewitt’s piano perfectly counters the dreamy tones and the percussion contributions from Willie Bobo, Armando Peraza and Alberto Valdes anchor the various Cuban and Caribbean-influenced rhythms. Tjader effortlessly remakes ballads like “Somewhere in the Night” and “Spring is Here,” the breezy vibes and piano seeping into your bones. A personal favorite is the self-titled opener, an all-too-brief take on a Chano Pozo/Dizzy Gillespie composition that is marked by Bobo’s shout-outs. Another highlight is Tjader’s take on Mongo Santamaría’s classic “Afro-Blue” with the additions of Donald Byrd’s trumpet, Jimmy Heath’s sax and Kenny Burrell’s guitar making it an exciting blend of jazz and African-influenced rhythms.

Antônio Carlos Jobim: Wave

Need an album to soundtrack a dinner date at home and you want to evoke warm breezes and hot nights? Then look no further than Antônio Carlos Jobim’s third and most successful album, Wave (1967). It exemplifies bossa nova (meaning new trend or new wave), a Brazilian style of music that’s like a slowed down samba combined with jazz. Jobim, a Brazilian composer and musician, was one of its pioneers. On Wave, there is the typical rhythmic guitar strumming and mellow percussion but also flute, trombone and strings. The cover art of a giraffe on an exotic beach oozes escape and passion, which is matched by the relaxed sophistication of the music. Highlights include the self-titled track and “Look to the Sky,” where the trombone is lonely and longing. “Triste” seduces with a gentle piano but the trombone cuts in briefly, echoing the melody with delicate insistence. The lone vocal track “Lamento” is also a highlight since it features Jobim himself singing, something he didn’t do very often. Do yourself and your significant other a favor and get this record.

Willie Bobo: Bobo Motion

Willie Bobo was a prolific percussionist and played with such greats as Dizzy Gillespie, Tito Puente, Mongo Santamaría, Cal Tjader and more. As a bandleader, Bobo is best known for blending Latin rhythms with soul and pop music, being one of the early innovators of boogaloo, soul-jazz and brown-eyed soul. 1967’s Bobo Motion has a mix of instrumental and vocal tracks (with Bobo on vocals) but also has Bobo getting more serious with jazz on standards like “Midnight Sun,” “Cute” and “Tuxedo Junction.” Pop music gets represented with a Latin jazz version of “Up-Up & Away” and Joe Tex’s southern soul stomper “Show Me” straight up burns with horns and relentless timbales. Mexican traditional “La Bamba” gets the Bobo treatment here and “Ain’t That Right” is a fantastic boogaloo number, a percussion-heavy cover of an Arthur Sterling song. Bobo’s guitarist, Sonny Henry, contributes two compositions “I Don’t Know” and “Evil Ways,” the first recorded version later made popular by Santana. Bobo Motion is an eclectic blend of jazz and complex Latin rhythms, illustrating exactly why DJs go digging for his records.

Astrud Gilberto: Beach Samba

Brazilian singer Astrud Gilberto is perhaps best known for contributing vocals to hit song “The Girl from Ipanema” from Getz/Gilberto, a 1963 collaboration between Stan Getz, her then-husband João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim. Eventually landing her own Verve contract, Gilberto’s solo albums don’t break any new ground but that’s kind of the point; her strength and freshness lie in her laid-back vocal delivery, which, along with the lush instrumentation, instantly evokes sandy beaches and refreshing cocktails. It’s all about the mood music, people. The appropriately titled Beach Samba (1967) is a prime example of this with its effortless bossa nova/pop style. While it didn’t generate the “Ipanema”-like hit that Verve desired, it’s a solid album that stays with you. The gentle “Misty Roses” seduces, “The Face I Love” enchants and there’s also the best duet between mother and son ever on her cover of The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “You Didn’t Have to Be So Nice.” Sometimes the simplest mood-setters are the albums you reach for the most.

Eddie Palmieri: Superimposition

Pianist Eddie Palmieri played in several bands including Tito Rodríguez’s band in the ’50s before forming his own band in 1961 and innovating the charanga style (a Cuban dance characterized by flute and violins) by replacing the violins with two trombones and thus helping to develop and popularize salsa music. Superimposition (1970) was Palmieri’s third album after breaking up his band to focus on more experimental styles of music composition. The first side of the album is comprised of three hot salsa numbers. “La Malanga,” “Pa’ Huele” and “Bilongo” mix Cuban rhythms, the two trombones dancing around each other. The trumpet solos from Alfredo Armenteros on “Pa’ Huele” and “Bilongo” are worth the price alone. But it’s the instrumental, improvisational jazz on the second side which gets the double take. The percussion loosely sets the rhythm on “Que Lindo Eso, Eh!” and the piano explores, never settling on a melody. “Chocolate Ice Cream” opens as a straight cha-cha-cha but the modal jazz piano and trumpet solos make it seem more like a jam. Palmieri’s dissonant piano takes a backseat to the percussion section on the last track, appropriately titled “17.1,” which is the average age of the three percussionists.

Mongo Santamaría: Sofrito

Sofrito (1976) is that cross between comfort food and complex delicacy. Blurring lines is exactly the genius of Mongo Santamaría, master conguero, percussionist and band leader. Born in Cuba before immigrating to the U.S., Santamaría took with him a style heavily influenced by African rhythms and was among those instrumental in the popularization of Afro-Cuban jazz in the 1940s-’50s on solo works as well as with Peréz Prado, Tito Puente and later Cal Tjader’s band. Initially dismissed upon release, Sofrito is actually very representative of the jazz movement in the ’70s and sees Santamaría in his 50s willing to experiment a bit, fusing Latin rhythms with funky beats and West African-influenced grooves along with electric keys and synths. Listen to traditional number “O Mi Shango” and be amazed. The perfect album for summer evenings with friends, “Iberia” wafts through open exotic windows, the chill is strong on “Cruzan” and then you’re transported to Cuban streets on “Spring Song” and personal favorite “Sofrito.”

Ray Barretto: La Cuna

One of the greatest congueros to ever slap the conga skins, Ray Barretto cut his teeth in the New York jazz world in the ’50s, eventually joining Tito Puente’s band when Mongo Santamaría left. After forming his own band in the ’60s Barretto popularized his version of charanga, pachanga and boogaloo music styles, which helped lead to the salsa craze of the ’70s. In addition to lighting up the dance floors, he also had a huge rivalry with Eddie Palmieri, their string of albums demonstrating a fierce desire to one-up each other. In the mid-’70s, Barretto left salsa behind (thanks to his band leaving him) and returned to melding these Latin influences with his first love, jazz. On 1979’s La Cuna, Barretto joins up with an all-star cast of players like Tito Puente, John Tropea, Charlie Palmieri, Steve Gadd and Joe Farrell, among others. La Cuna is a lesson on skill and musicianship; it’s a journey of electric funk and Latin rhythms. Highlights include “Doloroso,” Farrell’s hot sax on “Mambotango” and “The Old Castle,” where Tropea’s guitar tears it up.

Arturo Sandoval: Flight to Freedom

Arturo Sandoval, a brilliant trumpeter, made his American debut on Flight to Freedom (1991) after he defected from Cuba. Classically trained and long-influenced by jazz greats like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie (who became a friend and colleague after meeting in 1977), Sandoval struggled with the restrictions the Cuban government placed on him, controlling when and where he toured and the music he could play. As an artist he longed for expressive freedom. So when he was allowed to tour with Gillespie in Europe in 1990, and his wife and son were permitted to vacation with him there, Sandoval took advantage, enlisting the help of Gillespie and U.S. embassies to get him and his family to the U.S., where they eventually settled in Miami. Flight to Freedom unleashes Sandoval’s passion, where he is allowed to display his virtuoso abilities on Afro-Cuban bop (self-titled track and “Caribeno” are highlights), gentle samba (“Samba de Amore”), high energy numbers that even include some rock guitar (“Tanga”) and slow-burn ballads like “Body and Soul.” Sandoval’s passionate trumpet soars and smolders.

Marcella Hemmeter is a freelance writer and adjunct professor living in Maryland by way of California. When she's not busy meeting deadlines she frequently laments the lack of tamalerias near her house.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!