The 50 Best Record Stores In America is an essay series where we attempt to find the best record store in every state. These aren’t necessarily the record stores with the best prices or the deepest selection; you can use Yelp for that. Each record store featured has a story that goes beyond what’s on its shelves; these stores have history, foster a sense of community and mean something to the people who frequent them.

As with the rest of America, what’s come to be known as the Great LP Selloff started gathering momentum at Vintage Vinyl in St. Louis in the late 1980s. Compact discs, it had been determined by the corporations who earn dividends off of music, sounded better, were more durable and blah blah blah than the old format.

In most circles, vinyl was a lame-duck product. As with CDs today, sellers were lining up to ditch records they’d determined to be worth about as much as next week’s bar tab. Which is to say, to outsiders at the time, running a shop called Vinyl anything was akin to clerking at Sega City during the Playstation era. Society was fully embracing the digital revolution. Fuck records.

“The body isn’t cold yet,” wrote Billboard of the format in a 1990 story meant to project a little optimism. Wonderful, the corpse is still warm. Woo-hoo.

Those were heady times for those of us who felt otherwise, and the center of the St. Louis sell-off (and our buy-in) was in a former movie theater where a pre-R.E.M. Michael Stipe used to dress up as Frank N. Furter for Rocky Horror Picture Show screenings.

Vintage Vinyl has endured despite the typical peaks and valleys, and its success as it approaches its 40th year confirms a few brick-and-mortar truisms. Location is crucial. So is providing a communal gathering place. The 6,000-square-foot store sells as much old school R&B as it does hardcore punk, classic rock or grunge, caters to reggae and rap heads and soul lovers, has a devoted clientele who treat the shop like a sanctuary and a staff well versed in dealing with even the most finicky customers.

Zoom out and some reasons for its survival come into focus.

Set on Delmar Boulevard, a major thoroughfare that cuts like a stitched up ribcage through the middle of a segregated city, the shop resides along the symbolic dividing line between the largely black North Side and the mostly white South Side. Equidistant from Ferguson, the downtown St. Louis power center and the outer-ring suburbs where much of the monied class resides, the shop is one of those sacred spots in the city where circumstance is secondary to worshipping at the altar of music.

Pull back further to better understand the musical fertility — and the volume of used records — in the region: St. Louis is a half-day’s drive from Nashville, Memphis, the Mississippi Delta, Chicago and Kansas City. That’s a lot of music to be found.

It’s one reason why three excellent vinyl shops have white-knuckled their way on the retail rollercoaster across the decades. On the other side of town, the estimable Euclid Records is a jazz collector’s paradise (and a sister-store to its New Orleans location). And in midtown, the Record Exchange has accumulated a messy mass of rock, dance, R&B, pop, soundtrack and rap 12-inches. You might have to get your hands dirty to find some keepers.

Born in a farmer’s market stall in the early 1980s by partners Tom Ray and Lew Prince, Vintage Vinyl has been a destination for lovers of both new and used music ever since, as the store grew from stall to storefront to movie-house across its first two decades. Located in the University City enclave of the city, it stocks an impressive variety of new releases and has had an eye-popping selection of Record Store Day-related releases (the store served on the committee that launched the initiative).

Lew, who sold his share to Tom a few years back, got his start in New York as a gofer for the underworld-connected New York music figure Morris Levy. Tom, who DJs as the Soul Selector both locally and as the touring jockey for soul band Vintage Trouble, met his business partner while studying at Webster University in St. Louis. The two soon started dealing records. All these years later, Tom remains a singular figure. A self-described musical ambassador whose nickname is Papa, he has a tattoo of himself playing a harmonica on his forearm. He's currently collaborating with a Los Angeles-based production company on a vinyl-focused travel series.

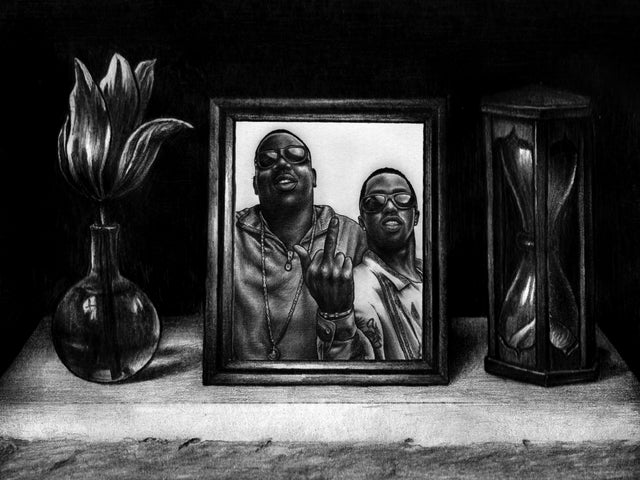

Before relocating to Los Angeles in the mid-’00s, I spent nearly a decade in the trenches buying used vinyl and ordering new indie, experimental and electronic music for the shop. Simultaneously earning income as a freelance writer when the rates weren’t crap, my life was changed by those years serving the community. I was surrounded by music 40 hours a week, being lectured by opinionated co-workers on the glories of Ann Peebles' records for Hi, the depth of Lee “Scratch” Perry’s bass tones or the primacy of Mos Def & Talib Kweli’s Blackstar project — that’ll open a life-long listener’s ears to the infinite avenues of exploration.

There’s no better spot for finding magic — or getting an unaccredited master’s degree in music history — than within a demographically varied community. Within a few miles of the shop are both some of the most violent neighborhoods in the country and securely gated communities dense with multi-million-dollar homes. It’s a short walk to respected academic institution Washington University in one direction and in the other, the gang-tagged spot where Nelly shot his breakthrough video for “Country Grammar (Hot Shit).”

In such neutral spaces, aesthetics are challenged daily. No opinion is more certain than that of a 55-year-old black woman hellbent on getting her Anita Baker fix. You haven’t been pooh-poohed in a conversation on great guitarists until a 75-year-old country-looking dude sets you straight on the efficiency of Merle Travis’ work on his early Capitol sides. That woman over there? She knows more about free jazz than most improv snobs twice her age.

We may not agree on much, but entering a store with a killer sound system, DJ booth, a few hundred thousand records at your disposal and James Brown’s Live at the Apollo pumping at good volume — that’s a pretty great feeling whether you’re a UPS guy, bar-back, heavy metal drummer, Sumner High dropout, college administrator or suburban skater.

Another choice feeling is being the used buyer on a day when an aged guy lugs in a few crates of records — then flipping through them, adrenaline rushing, to find well-tended Impulse, Blue Note and Stax records. Or greeting a done-with-it punk fan who’s ditching her case of Drunks with Guns and Misfits 45s. Or arriving for an evening shift to find that a colleague just bought a former Chicago house DJ’s collection of old Dance Mania, Relief and Cajual 12-inches. A few hundred of them, bought at fifty cents a piece and headed for the 99 cent bin. (Thanks to a very generous employee discount, most never made it onto the floor.)

Across much of the 1990s, I’d clock in at 10 a.m. on a Saturday, still buzzing from last night’s warehouse party, open the shop and greet men and women of all ages and races as they wheeled in hand-trucks stacked butt-high with records.

Some days we’d see 20,000 records come through, sellers lining up to ditch perfectly beautiful copies of James Brown, Led Zeppelin, Spinners, Lucinda Williams, Talk Talk, Joy Division — you name it — records. Tattered but clean-enough copies of Free Your Mind and Your Ass Will Follow that we’d put out for $4.99. Inevitably, a shopper would hit the Funkadelic section, pull the record out, slack-jawed, as she gazed in disbelief at the find.

Those first-crush moments have occurred daily. Psyches seeking a kind of sustenance that can’t be had through easily accessed portals.

He’s gone now, but for a long time there used to be a Jesus-looking metal dude in St. Louis who spent his days hiking up and down Delmar Boulevard rocking out on his Discman. Always wearing his headphones, he would drum-solo down the road as commuters rubber-necked, his arms reaching for imaginary splash cymbals and banging invisible snares, his feet stomping, legs kicking, head banging. We used to joke that he was probably listening to the Carpenters.

Lost in music, the guy was a one-man boogie crew who seldom stopped for breath, but when he entered Vintage Vinyl, he’d ditch the headphones, stop dancing and browse the stacks, like outward expression of his musical obsession was no longer necessary. As if the frequencies circulating in the store were enveloping him, he’d browse with a calmness that belied his Keith-Moon-on-meth actions of moments earlier. He seldom bought anything, but that didn’t matter. His lost-in-music commitment conjured a kind of magic into the environment.

In such moments within such spaces, music’s power to engage the very air around us confirms its majesty. Vibrating frequencies, after all, have wended their way from a long-gone studio in some faraway place, onto a piece of spinning vinyl, through a needle, into an amplifier and out of speakers, activating our eardrums before seeping into our skulls.

Is it any wonder the body of vinyl wasn’t yet cold when Billboard offered hope in 1990?

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!