The 50 Best Record Stores In America is an essay series where we attempt to find the best record store in every state. These aren’t necessarily the record stores with the best prices or the deepest selection; you can use Yelp for that. Each record store featured has a story that goes beyond what’s on its shelves; these stores have history, foster a sense of community and mean something to the people who frequent them.

It’s a rainy day when I visit Melody Supreme, a record store that sits upon the corner of Fourth and Water Street on Charlottesville’s pedestrian Downtown Mall. At first glance, the Fourth Street crossing is a largely unassuming strip of real estate lined by comfortingly plush businesses, like the jeweler and earthy pop-up boutique that flank Melody Supreme. It’s only when I get closer—when I can see the chalk scribbles on the brick, the damp flowers piled up on the pavement—that it becomes clear something else happened here.

It’s been almost three months since the events of August 12, when a white supremacist rammed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters in an attack that killed 32-year-old paralegal Heather Heyer and injured 19 others. That violence took place virtually on Melody Supreme’s doorstep. Yet while the story of August 12 is inextricably tied to Charlottesville’s history of barely-buried hatred and bigotry, the miracle of Melody Supreme comes from an inverse kind of constancy—it lies in its seemingly contradictory ability to be both a deeply embedded anchor of the city’s music community and a much-needed sanctuary from the outside world.

When I’d first arrived in Charlottesville as a student last year, I’d admittedly felt a little alien. It wasn’t a particularly new feeling—a good chunk of my high school graduating class had ended up at the University of Virginia, which is the kind of sprawling, prestigious school that photographs perfectly during autumn and possesses a tangible sense of history in its neoclassical architecture and charming traditions (students affectionately refer to its founder, Thomas Jefferson, as “T.J.” or “Mr. Jefferson”). It feels particularly idyllic if you’re coming from the blandly upscale D.C. suburbs where I grew up and are willing to forget that the heart of campus (or “Grounds,” in UVA parlance) was literally built with slave labor.

I bought into that myth even as I knew how manufactured it was; like most unassuming teenage Asian girls hailing from suburbia, I felt a compulsive need to prove that I deserved to take up space in such a storied place. I wasn’t effusive enough to be a sorority girl, so I decided to apply to the student radio station half on a whim, and felt oddly fraudulent when I got accepted. I was particularly skilled in the art of standing nonchalantly in the kitchen or on the chilly front steps during house shows, making light conversation with people who were more beautiful and self-assured than I was, while giving off the impression that I belonged. While I’d always liked to think of myself as a person who had overcome the embarrassingly adolescent need to fit in, upon coming to college I’d realized, with horror, that I definitely still wanted to be cool—or at least for the people I liked to think I was.

In reality, my musical taste was decidedly unsophisticated—the first album I’d ever owned was the High School Musical soundtrack, I earnestly loved “We Built This City” and all the synth-soaked '80s singles of its ilk that even my mom thought were tacky, and I’d cried multiple times while watching Hamilton on Broadway with my high school drama class. The boy who was my not-boyfriend at the time (but whom I still desperately wanted to like me) was a musician who would occasionally send me samples of his work and ask for my feedback, which I always delivered in the kind of vaguely faux-poetic word salad of phrases like “shimmery and evocative” or “like early Modest Mouse placed inside a sensory-deprivation tank” in order to disguise my nonexistent technical knowledge. But I loved the weirdly cerebral sense of discovery that came with finding something new to listen to, even if I wasn’t quite sure why I loved it—I only found out who Philip Glass was when he was an answer to a quiz bowl question, and I realized that I unironically loved the compositions of the 12th-century nun Hildegard of Bingen after her name came up in a class on women in medieval Christianity.

Furthermore, it was my roommate who was the bona fide vinyl collector, not me. I felt like an imposter whenever conversations turned to hi-fi or limited pressings, but nevertheless grateful that I’d been allowed to stay along for the ride. The first time we went to a record store together, I had absolutely no idea what I was looking for.

As it turned out, Melody Supreme was just alien enough to feel like home to me. At nearly eight years old, the store is relatively young and has an unconventional origin story. It was founded in 2010 by Gwenael Berthy, a French-born photographer who made the decision to break into the independent record store business around his 40th birthday. After arriving directly from France, he briefly lived in Richmond before acquiring the downtown Charlottesville space that Melody Supreme now occupies—a painstaking process that reportedly took nine months of preparation. At the time he moved, he’d known nobody in Charlottesville.

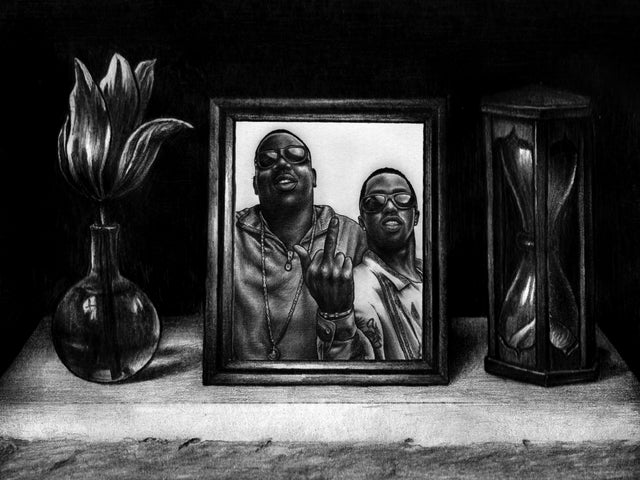

Melody Supreme’s success is a testament to Berthy’s exacting eye for detail, which is evident in the store’s thoroughly curated record selection. When I finally escape the ceaseless drizzle and raise my head as I step through its door, I’m struck by an overwhelming urge to explore while also knowing that I could spend hours in here without unearthing half its mysteries.

Despite the bright, clean retail space being small enough that its entirety can fit lengthwise within my field of vision, browsing its deep bins of vinyl carries the giddy thrill of sightseeing in a secret museum. The first name I see in the classical section is unfamiliar—before the requisite Bach and Beethoven, I find the Frottole of Bartolomeo Tromboncino, a Renaissance-era composer and trombonist who I later learn notoriously murdered his wife and was employed by Lucrezia Borgia. The adjacent box, labeled “20th Century Avant Garde Electronic Moog,” contains a 1978 record called Computer Generations. It has a bright, abstracted orange and blue cover and track titles like “In Memoriam Patris” and “Synapse for Viola and Computer” that evoke alien wonders, even within something so ostensibly dated. There’s a kind of enchanting freedom in being able to embrace how much I don’t know. I love getting to be a complete tourist here, freed from the perceived obligation of establishing any superficial indie cred. The “recommended” display heartily endorses the self-titled LP of a Japanese krautrock band called Minami Deutsch, and I scrawl the name on my hand to search up later.

Elsewhere, in a cardboard box brimming with seven-inch singles, I unearth a copy of The 5th Dimension’s “Living Together, Growing Together,” a tune penned by Burt Bacharach and Hal David for the infamously bad 1973 film Lost Horizon. It’s wrapped in a sleeve bearing sugary, pastel-toned art of a rainbow sprouting from flowers and clouds, all under a soaring RCA logo. Among a bin of movie soundtracks, there’s a still-shrinkwrapped soundtrack to Bad Channels, a campy 1992 sci-fi spoof that was likewise critically reviled but happens to boast an original score by Blue Öyster Cult.

Behind it, I inadvertently find the soundtrack to Phenomena, one of my favorite movies—it’s a 1985 horror flick directed by Dario Argento and starring a pre-Labyrinth Jennifer Connelly as a psychic schoolgirl in Switzerland, heavy on gory murders and gross-out bug imagery. The score by Goblin is loaded with the sort of eerie '80s-slasher synths I’ve always been a sucker for, and Berthy seems to notice I’ve been longingly caressing the album for a while. He mentions that it’s an exceptional find, and I eagerly ask if he has any of the other soundtracks to Argento movies, like the better known Suspiria or Deep Red, but he says no. Still, the heady rush of this discovery makes me feel unstoppable.

I know there’s no objective way I can justify purchasing these records, but they nevertheless seem to hold some arcane, tempting power. They’re fascinating not simply for their kitsch or curiosity but as artifacts in themselves—I find myself wondering about each record’s lineage of owners, the odysseys they underwent to end up in Charlottesville. When asked by a local blog what makes vinyl different from other music formats, Berthy once answered that it was “the tangibility, the carnal aspect of vinyl that other medias don’t have: the gorgeous cover art, the liner notes and back-cover literature, and this glossy round black disc that we place gingerly on a turntable.” Despite the fact that I don’t even own a record player, the adventure of that physical ritual still seems to pull me in.

Additionally, the vast breadth of Melody Supreme’s collection doesn’t neglect local bands. The Charlottesville music scene is by no means large, but I still don’t recognize some of the names I find here. I know New Boss, a rollicking psych-tinged rock band that’s still fairly active playing gigs around town, but not Red Rattles or Invisible Hand, the former a garage-soul duo and the latter a slick power-pop four-piece once hailed, the same year Melody Supreme opened and six years before I moved here, as “Charlottesville’s favorite indie rock band.” I try to dig up more via impromptu Google search, but both groups seem considerably lower-profile at the moment if not totally defunct. Their impermanence feels oddly sad, and yet again I have to rein in my urge to snatch up every album in the crate in an attempt to keep myself from forgetting their stories.

It’s still raining by the time I finally leave, but this time the wet, stinging cold somehow feels sharp and clarifying, not numbing. I find myself taking note of the world’s smallest details. When I cross the street to take a closer look at the makeshift memorial, I see a pristine red Solo cup full of bright orange carnations and golden roses among the older, browned flowers. Amid the calls for love and resistance and countless promises to remember Heyer, there’s a chain of pale bluebells chalked across the brick. Nobody has forgotten what happened here, but there’s room for these small, unexpected wonders even within the solemn remembrance.

Next up, we travel to a record store in New York.

Aline Dolinh is a writer from the D.C. suburbs with an earnest passion for 80s synthpop and horror movie soundtracks. She is currently an undergraduate student at the University of Virginia and tweets @alinedolinh.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!