Cardi B, Boosie, and Jean Grae & Quelle Chris And The Best Rap Of April

Every month, we round up the best releases in rap music. This month's editions breaks down new albums from Cardi B and more.

Henry Canyons: Cool Side of the Pillow

Henry Canyons is self-possessed. The New York-raised, Los Angeles-based rapper tends toward funkier, more kinetic modes of boom-bap and its millennial offshoots, but is beholden to no particular vocal tradition. He’s someone with chops but little urge to show off for its own sake, a technician with an eye on the larger picture. Cool Side of the Pillow is bright and warm and full of energy; it comes after La Cote West, an EP Canyons made while on an artist’s retreat in French Basque Country. The psychological reimmersion to a fractured America pokes through on the closing song “To the Dreamers,” which is syntactically slippery but, at its core, painfully clear.

Jean Grae & Quelle Chris: Everything’s Fine

Since he broke through to some national renown with 2013’s Ghost at the Finish Line, the Detroit-bred Quelle Chris has distinguished himself as one of indie rap’s most brilliant auteurs. Imagine putting out a string of solo and instrumental records, each increasingly ambitious (and increasingly weird), and carving out a career in the midst of aesthetic and economic sea changes that swallow up even your most talented peers. Now imagine doing all that and maybe not being the best rapper in your marriage. What makes the pairing––musically, I mean––of Quelle and Jean Grae so fascinating is that they’re on parallel, equally subversive courses in decidedly different lanes. Jean is a New Yorker who was in Unsigned Hype and who can slip into fluent, classicist tongues, but who injects them with color and verve and wit. Everything’s Fine is ultimately an album about mental health, and not only in the way that all rap albums are about mental health. It’s biting but sincere, aspirational but world-wearied.

Boosie Badazz: Boonk Gang

It’s tempting, although probably not productive, to compare the post-prison careers of Boosie and Gucci Mane. Where Gucci said yes to everything and radiated joy en route to the most bankable period of his career, Boosie spent month after grim month rapping sharply, bluntly, sometimes shrilly about his demons to a diminishing audience. (It should go without saying that both courses are completely understandable for men in Gucci and Boosie’s situations; if either or both of them wanted to tap out for the next 40 years and never release another song, that would be, too.) Boosie’s followed a staggeringly good comeback mixtape, Life After Deathrow, with a series of uneven full-lengths, but on Boonk Gang has finally stopped squeezing the bat too tight: he flits from Aaliyah’s beats to Kendrick Lamar’s, to B-Legit’s and back again. He’s also stopped squeezing the bat too tight, and is instead rapping gleefully about being a side piece and slipping into Rihanna’s pockets and, on the cover, snatching his more famous peers’ plaques for himself.

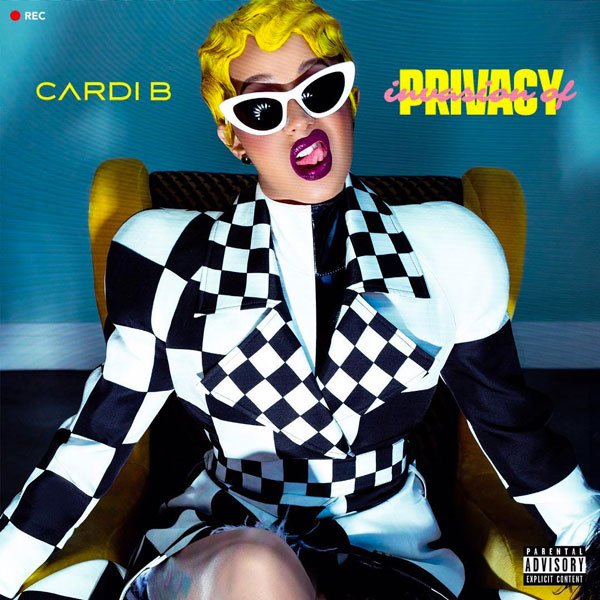

Cardi B: Invasion of Privacy

Invasion of Privacy is the type of album that could only exist on a major label. That goes for the stunt casting, sure––SZA, 21 Savage, DJ Mustard, YG, Chance the Rapper, so on and so on––but it’s also true of the way Atlantic has taken an immutable, bursting-at-the-seams personality like Cardi B’s and tried, almost manically, to filter her through every tried and market-tested lense it has at its disposal. “Bodak Yellow,” of course, is the case study, a song that––if it were reduced to sheet music––would be a direct lift of an another artist’s work, but is made distinctly Cardi’s own through her voice, taunts, syntax, shoes. That same strategy is employed frequently on her debut album, often to satisfying results: opener “Get Up 10” is traced from Meek Mill’s legendary Dreams & Nightmares intro, but could the introduction to Cardi be any more Cardi?

YoungBoy Never Broke Again: Until Death Call My Name

Though it hasn’t spawned a genuine star in more than a decade, New Orleans still enjoys an outsize influence over modern rap, from the mainstream to the experimental edges, its sounds and sensibilities osmosed across state lines and through Wifi waves. The same can’t be said of Louisiana’s capital. For most of its history, Baton Rouge’s rap scene has been hermetically sealed, with stray shards of Boosie or Webbie’s catalogs slicing through the din. YoungBoy Never Broke Again follows Kevin Gates as that city’s great national hope (a status that Gates held himself until incarceration slowed him down). YoungBoy, slowed by his own legal troubles, is perhaps too faithful to Gates and to Young Thug, but has occasionally struck gold––see last year’s “No Smoke.” Until Death Call My Name is a step forward in every way, written personally and delivered viciously. Highlights include “Diamond Teeth Samurai,” which reimagines Tha Block Is Hot as a beef traced through Instagram stories.

Cavalier: Private Stock

Speaking of New Orleans, that’s where Brooklyn native Cavalier has holed up to write and record his last couple of underheard (and at times overwhelming) releases. Private Stock, a full-length album produced in its entirety by the singer Iman Omari, is a cool, heady listen that rewards close attention but has enough musical depth to settle into bones in most settings. Cav is, in many ways, an extraordinary rapper, athletic and agile but never in a way that crowds his writing out of the picture. The most essential tracks are the pair with Quelle Chris, with whom Cav had previously teamed up on Niggas Is Men, one of the best underground rap records of the decade.

Paul Thompson is a Canadian writer and critic who lives in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in GQ, Rolling Stone, New York Magazine and Playboy, among other outlets.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!