Os 10 melhores álbuns de Willie Nelson para ter em vinil

Willie Nelson está na indústria há tanto tempo que, essencialmente, ele se transformou na própria versão da música country de uma lenda raconte. Infelizmente, isso frequentemente significa que ele é reduzido a uma piada, seja por causa de todo aquele caso de evasão fiscal ou por seu status como o avô que fuma maconha de Nashville.

nMas Nelson também é uma das maiores lendas vivas da música. A maioria o conhece pelas canções que ele transformou em alguns dos padrões mais reconhecíveis da música country, de "Always on My Mind" a "On the Road Again." O que eles podem não saber é que Nelson é um dos produtores de álbuns mais prolíficos da indústria da música. Seu último LP, God’s Problem Child, foi seu 61º álbum de estúdio. Seu primeiro, …And Then I Wrote de 1962, completa 55 anos este setembro.

nA maioria das pessoas talvez não esteja ciente de que Nelson é um colaborador consumado. De fato, poucas estrelas que brilharam tão intensamente e por tanto tempo quanto Nelson mostraram disposição para compartilhar os holofotes, seja com participações especiais (ele apareceu no álbum de Natal de Kacey Musgraves no ano passado) ou álbuns de colaboração de longa duração (incluindo gravações com artistas como Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard e Waylon Jennings). Na verdade, muitos dos álbuns mais recentes de Nelson foram oportunidades para ele convidar uma série variada de parceiros de dueto ao estúdio, de Sheryl Crow a Snoop Dogg.

nCom cinco décadas e meia de trabalho sob o seu comando e literalmente dezenas de álbuns creditados, o Willie Nelson de 84 anos não é um artista que você pode entender em uma semana, um mês ou até mesmo um ano. No entanto, se você está buscando explorar o catálogo de um dos pioneiros da música country, esses 10 álbuns são um bom lugar para começar.

The Words Don’t Fit the Picture (1972)

The first 11 years of Willie’s recording career—from 1961 to 1972—were ultra-prolific, seeing the release of no fewer than 15 albums. The majority of those were released by RCA Records, which scooped Nelson up after the success of his first two LPs on the Liberty Records label. Nelson’s RCA years saw minor success—he joined the Grand Ole Opry and scored a few middle-of-the-chart hits—but didn’t mark a meteoric rise to superstardom. Frustrated by his middling success, Nelson actually retired from music in 1971, only to come back the next year to deliver two more albums for RCA. The return was vital, as 1973 would prove to be one of the most important years of Nelson’s career. He’d sign with a new label, release his breakthrough LP, and form the backing band that still plays on his records and tours to this day. But 1972 was the calm before the storm, and the albums he released that year—particularly the first one, The Words Don’t fit the Picture—are fascinating for showcasing Nelson at the moment before he became THE Willie Nelson. “Will You Remember?” is especially stunning, a wistful lover’s farewell that sounds even more heartbreaking when you know that the guy who recorded it had very nearly given up music for good. Thank the country music gods he didn’t.

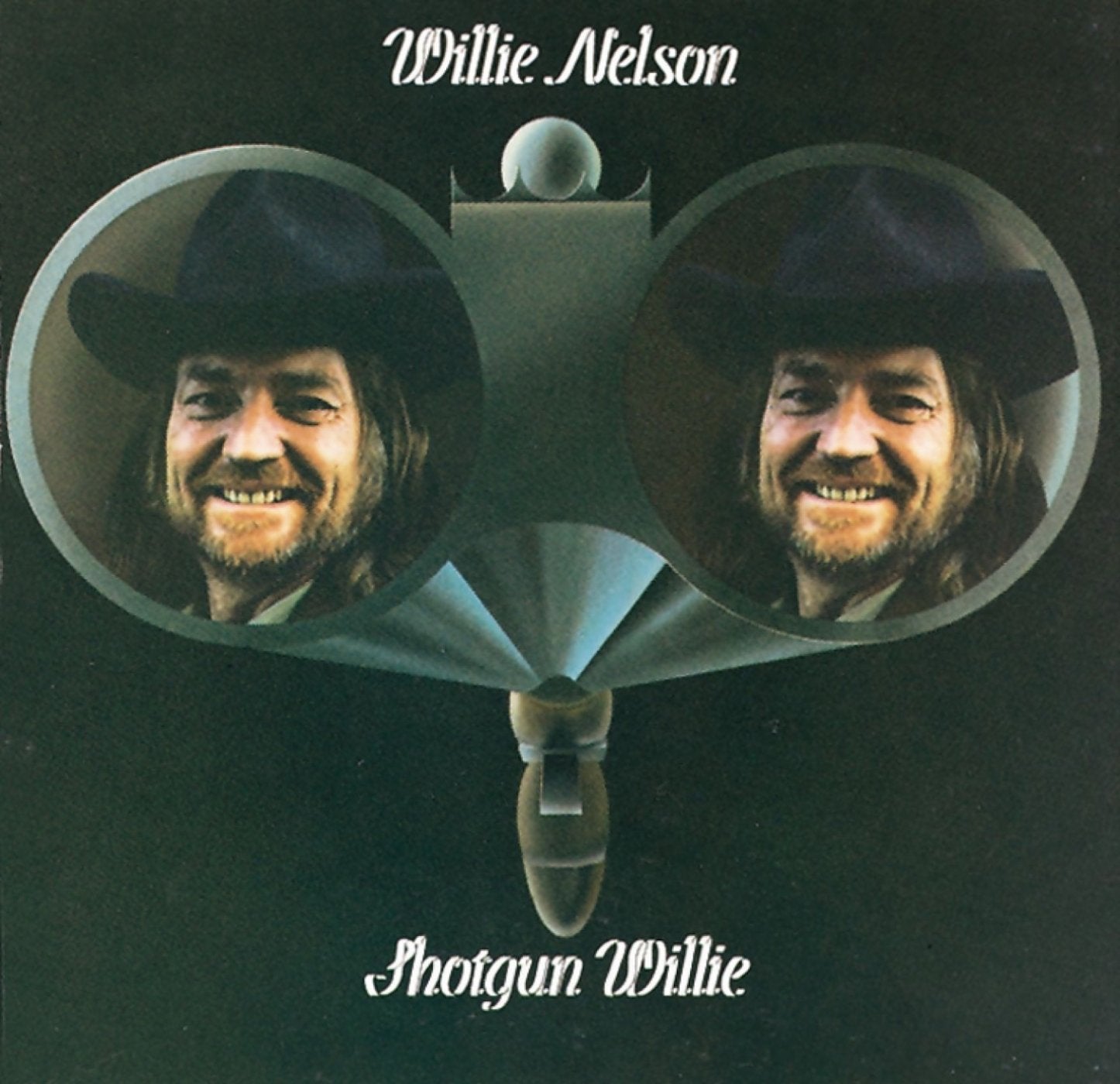

Shotgun Willie (1973)

After a falling out with RCA, Nelson met Jerry Wexler, the influential Vice President of Atlantic Records and the man who coined the term “rhythm and blues.” Wexler played a brief but important role in Nelson’s career, signing him as Atlantic’s first-ever country artist, and perhaps pushing his sound in a more R&B-focused direction. The result is an album that sounds a good deal livelier than the purer country records from earlier in Nelson’s catalog. The title track bursts with horn arrangements, while “Whiskey River” is a bluesy gem that stands as one of the most instantly infectious songs Nelson ever recorded. The dynamic sound of the record—which blended classic country, rockabilly, jazz and R&B—was radical compared to most of the music that was coming out of Nashville at the time. It not only served as Willie’s commercial breakthrough, but it also made him one of the faces of the adventurous, uncompromising “outlaw country” subgenre—a movement still viewed romantically today by those who reject the blatant commercialism of Music Row.

Phases and Stages (1974)

If you want to know how Nelson pushed country music further than just about any artist who came before him, listen to Phases and Stages. A divorce record that narrates the dueling perspectives of its heartbroken protagonists—the woman’s perspective gets side one, while the man’s plays out on side two—Phases and Stages was one of the first-ever concept records in country music. More than just being groundbreaking, though, Phases and Stages is compelling for how Nelson inhabits and understands the characters. The stereotypical country song is a guy singing about how his woman broke his heart, took his dog and drove off in his truck, but Phases and Stages puts the blame for a divorce squarely on the shoulders of the man. Side one depicts a long-suffering wife finally ditching her husband. It’s a justified move: this guy is a philandering drunk, and can’t even help out with the dishes! The woman gets a happy ending: She gets back out there, dances to honky-tonk music (“Sister’s Coming Home/Down at the Corner Beer Joint”), and finds a new boy in “(How Will I Know) I’m Falling in Love Again.” The husband drowns his sorrows in booze (the album’s first single, the bluegrassy “Bloody Mary Morning” is essentially the 1974 version of Dierks Bentley’s “Drunk on a Plane”) and dwells in self-centered sadness until the record ends. The fact that the male character gets no redemption at all underlines the surprisingly feminist tilt of the record as a whole.

Red Headed Stranger (1975)

In the song “Record Year,” Eric Church thanks his ex for sending him reeling toward his record collection and helping him, among other things, rediscover Red Headed Stranger. Most Nelson fans probably don’t need to rediscover this 1975 LP, which is often labeled as his creative peak. After splitting the early years of his career between RCA and Atlantic Records, Nelson and his manager somehow negotiated a deal with Columbia that gave him complete creative control over his work. His first move was to create Red Headed Stranger, a sparse concept record about a man who kills his unfaithful wife and her lover after discovering the affair. Eventually, the stranger finds love again, and the record ends with the titular character old and gray, spending time with a grandchild. It’s a murder ballad expanded to full-album length, but it’s a classic not because of the blood and intrigue, but for its achingly heartfelt portrayal of a man getting over his broken heart. Songs like “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” and the harmony-drenched “Can I Sleep in Your Arms” are among Nelson’s most gorgeous recordings ever, and the former even became his first number one hit.

Waylon & Willie (1978)

The story goes that Waylon Jennings started kicking around the idea for this album by overdubbing his vocals on old Nelson recordings. The two outlaw country superstars had already worked together a few times at this point: Nelson had served as a co-producer on Jennings’ This Time album, and the two had written together and duetted a few times before. But it wasn’t until Jennings called up Nelson’s label and pitched the idea of full duets record that Waylon & Willie was born. It was the first of many Nelson albums that would be driven by collaboration, and is still arguably the best. The most famous cut is “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow up to Be Cowboys,” an undeniable country standard. Perhaps the most fascinating track, though, is the cover of “Gold Dust Woman,” originally immortalized by Stevie Nicks at the end of Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 opus Rumours. Where the Mac version is ghostly to the point of sounding possessed, Waylon and Willie turn it into a swampy, saloon-ready jam, with tipsy keyboards and plenty of pedal steel.

Stardust (1978)

Nelson’s status as an interpreter of songs written by other people has always been central to his identity as an artist. While Nelson is a songwriter, he has also frequently recorded covers or cut songs penned by fellow writers throughout his career. Even concept records like Red Headed Stranger have their fair share of songs written by other people. Stardust puts the spotlight completely on Willie Nelson the interpreter. An album full of pop standards—such as “Georgia on My Mind,” “Unchained Melody” and “Moonlight in Vermont”—Stardust wasn’t popular among Columbia executives, who thought it ran counter to what Nelson’s fans wanted to hear. (After all, what screams “outlaw” less than recording an album full of well-known pop songs?) Ultimately, though, Nelson was right: Stardust went platinum and ended up being one of the most singular and beloved albums in his catalog. Produced by the legendary Booker T. Jones, the album has a smooth, lush sound that still sounds fresh and modern today—even when much of Nelson’s earlier material has come to sound a bit dated. Every song is beautifully arranged and sensitively sung, but Nelson’s take on “Georgia on My Mind” is the highlight, punctuated by one of the most stunning harmonica solos ever captured on tape.

Always on My Mind (1982)

Some Nelson fans are not particularly fond of Always on My Mind, and it’s not all that hard to see why. Imagine a guy like Sturgill Simpson recording an adult contemporary record today and you have a pretty good idea of what it was like for Nelson, a leader of the outlaw movement, to cut an LP so clean and anaesthetized back in the 1980s. In fairness, this record sounds incredibly dated, its trappings of 1980s pop so overbearing and cheesy—from the Journey-style guitarwork on “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” to the hefty backing vocal arrangement on the legendary title track. But “Always on My Mind” is still arguably Nelson’s signature song, a massive hit that remains a crossover standard all these years later. And “Always on My Mind” might not even be the best song here! On the contrary, the record is at its strongest when producer Chips Moman lets the songs breathe a bit, like on the sparse acoustic cover of “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (which bears one of the best Nelson vocal performances ever) or the raw, man-at-the-end-of-his-rope ballad “Last Thing I Needed First Thing This Morning (which Chris Stapleton covered on his most recent LP).

Pancho & Lefty (1983)

After Waylon & Willie in 1978, Nelson caught the bug for collaborative projects. In the next few years alone, he made duet records with the likes of Leon Russell, Ray Price and Waylon Jennings (again), as well as The Winning Hand, an oddity that featured Nelson alongside Kris Kristofferson, Dolly Parton and Brenda Lee. As far as late-’70s/early-’80s country is concerned, that list of musicians is a murderer’s row. With that said, the next truly great collaborative record on Nelson’s resume didn’t come until January 1983, when he teamed up with Merle Haggard for Pancho & Lefty. The title track is arguably the greatest song in Nelson’s oeuvre, an epic ballad about a Mexican bandit and the associate who betrays him. (Despite the violence, the song features one of the sweetest-sounding chorus refrains in country music.) Townes Van Zandt wrote the song in 1972, but Nelson and Haggard were the ones to turn it into a standard, with their duet version giving both characters new levels of depth and feeling. The 2013 version by Jason Isbell and Elizabeth Cook might be even better, though, underlining the aching, Springsteenian tragedy lurking in the lyrics.

Teatro (1998)

In 1996, Nelson recorded a sparse, mariachi-infused collection of songs called Spirit. It was unlike anything he’d ever done before, devoid of drums and electric guitar and made up entirely of original compositions. Unfortunately, Spirit has never been pressed on wax, but Teatro—which came two years later—is similarly singular and splendid. While the record keeps some of Spirit’s mariachi vibe, it strands it in an almost otherworldly place. Thank U2 producer Daniel Lanois, who stepped behind the boards for this record and helped Nelson create the most sonically ambitious work of his career. Like many Lanois productions, the record is dusty, atmospheric and sparse, built around very prominent drum parts (see the sublime “Darkness on the Face of the Earth”) and muggy, distorted electric guitar (“The Maker,” a cover of a Lanois original). In that sense, Teatro is a completely different beast than the barren, desolate Spirit, which had no percussion or electric guitar at all. It’s that dichotomy between these two records—between the things they share and the things they absolutely don’t—that makes both so fascinating. Teatro especially feels like an out-of-comfort-zone moment for Nelson, and his catalog is stronger for containing such a distinctive left turn. Teatro also stands out in Nelson’s catalog due to the presence of the great Emmylou Harris, who lends stunning backing vocals to 10 of the 14 tracks.

God's Problem Child (2017)

You aren’t supposed to sound this raucous on your 61st album, especially when you’re 84 years old. (In fairness, God’s Problem Child came out the day before Willie turned 84.) Never one to take himself too seriously, Nelson’s working title for the album was I’m Not Dead. He ultimately changed it to God’s Problem Child, but we still get the objectively funny “Still Not Dead” as a consolation prize. “I woke up still not dead again today / The news said I was gone to my dismay / Don't bury me, I've got a show to play” he quips in the third verse, humorously acknowledging the internet hoaxes that often spring up surrounding his mortality. But God’s Problem Child also sees Nelson grappling with old age and the inevitability of death in more understated, vulnerable ways. “It Gets Easier” plays like Nelson reminding himself not to waste the numbered days he’s got left, while the heart-wrenching “He Won’t Ever Be Gone” is a reflective and surprisingly hopeful ode to the life, spirit, and lasting legacy of Merle Haggard. It’s not surprising that the album has received near-universal acclaim, or that it’s been frequently lauded as Nelson’s best work in almost 20 years.

Craig Manning is a freelance writer with bylines at Chorus.fm, Behind the Setlist, and Modern Vinyl. He's left specific instructions to be buried alongside his guitar and his collection of Bruce Springsteen records.

Related Articles

Junte-se ao Clube!

Junte-se agora, a partir de 44 $Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!