誕生於1990年左右倫敦的公園酒吧,英倫流行的蒼白流行歌曲為英國生活提供了完美的背景音樂。不過,並非所有的一切都是陰霾與悲觀:像Oasis、Blur和Suede這樣的樂隊展現出一種世界前所未見的自信。他們在競技場上的頌歌汲取了披頭士和曼徹斯特音樂的數十年影響,但他們為自己定義了獨特的風格。這個亂糟糟的音樂場景迅速變得如此成功,以至於似乎只是時間問題就會燃燒殆盡。英倫流行在90年代結束時確實漸漸消逝,但它的火焰從未真正熄滅。正如這十張專輯所證明的,英倫流行最大、最優秀樂隊的音樂和心態仍然是懷舊的源泉,渴望著早已失去的日子,同時也是對未來美好日子的希望。

The La’s: The La’s

The genre would soon become a phenomenon independent from other musical forces, but Liverpool four-piece the La’s eponymous 1990 debut managed to form a bridge between Britpop and the earlier eras of riffs and raves. While also taking from the Stone Roses and the Smiths, straightforward songs like “Son of a Gun” combine The Beatles with the Kinks to create a cocktail bands like Oasis would commercialize in the following years. With blatantly blissful ballads such as “There She Goes,” the La’s predicted what was to come in British guitar music. The band made the waves on which Britpop bands would ride for a decade. Sadly, the band, which was fronted by Lee Mavers, wouldn’t be around to witness it themselves. Around 1992, the La’s disappeared without a trace, but they sure did leave a mark on British music.

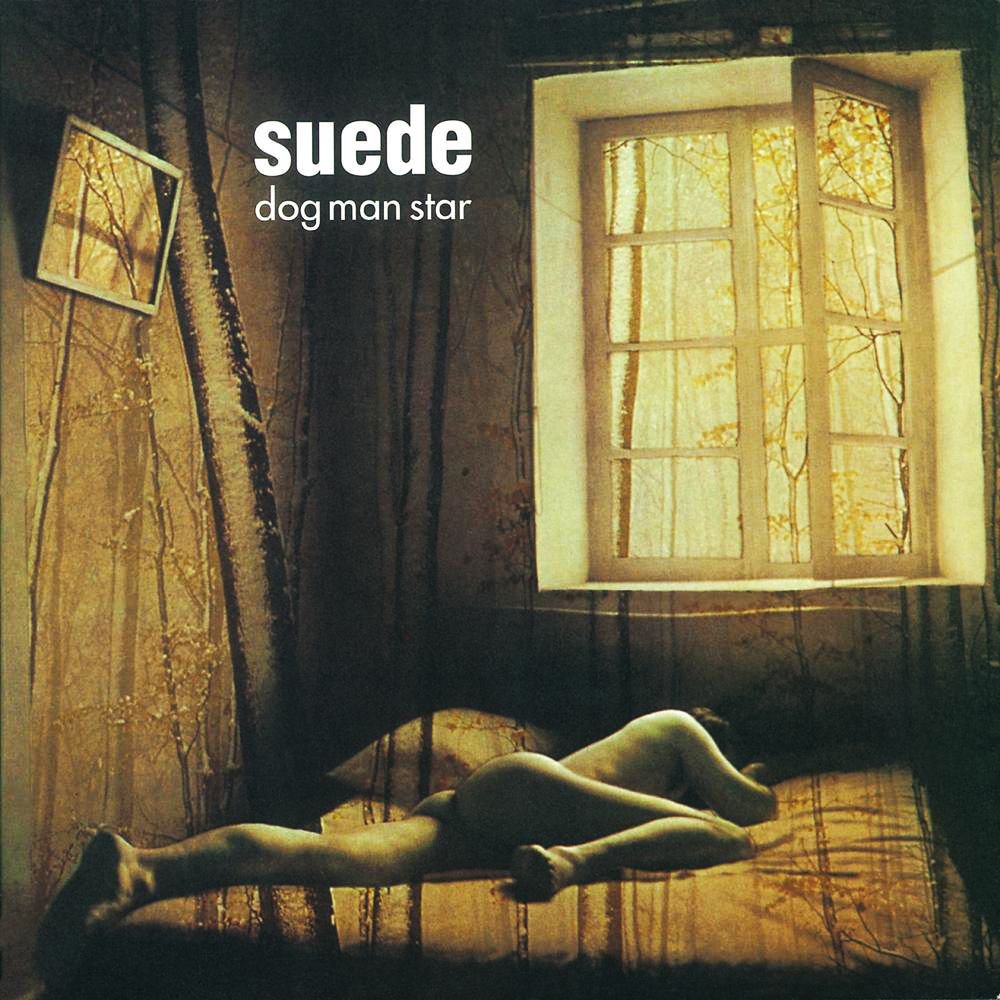

Suede: Dog Man Star

The first person to take advantage of that mark was Brett Anderson, Britpop’s first big star. The Suede frontman featured on the cover of Select’s April 1993 “Yanks Go Home!” issue, an anti-grunge call to arms by British bands. Only one year later, Anderson had become disillusioned with the stardom he’d found himself stuck in. He’d fallen out with Suede’s songwriter and guitarist Bernard Butler and created 1994’s Dog Man Star as an account of his own isolation. The album, consisting of sadscapes and the sexiest of symphonies, turned into some sort of breakup record when it wasn’t finished yet when Butler eventually decided to leave the band behind. Dog Man Star sure might seem somewhat excessive. Then again: preposterous was kind of the point with Suede, a band who sanctified sadness.

Blur: Parklife

As soon as one star fell from the Britpop firmament, another one gladly took its places. With a diverse palette of pop songs, London boys Blur became the poster boys of Britpop. Their Parklife became a colourful catalyst behind the process of moving guitar music from the margins to the mainstream. On the 1994 album, Blur showcased the depth and diversity they’d be hinting at on their earlier albums, with disco songs like “Girls & Boys”, ambitious anthems like the title track and the most British breakup songs ever. The once shoegaze-y art school students suddenly became the stars of Britain and built Britpop as we now know it. Well, Oasis might have had a hand in that as well, but while their commercially successful work stayed relatively conservative, Blur, from Parklife on, were all about creativity.

Oasis: (What’s The Story) Morning Glory

One of the most stubborn myths in music is that it’s hard to write a successful second album. If there’s any band who has proven that wrong, it’s Oasis, not only one of the biggest bands of the Britpop movement, but one of the biggest rock bands to ever do it. The Gallagher brothers’ 1995 classic (What’s The Story) Morning Glory, the successor to 1994’s Definitely Maybe, proved once and for all that practice makes perfect indeed. The album, featuring the iconic-turned-ironic "Wonderwall" and "Don’t Look Back In Anger," is a collection of huge hits, but also a set of surprisingly reflective songwriting by the brilliant Noel Gallagher. Album closer “Champagne Supernova,” for instance, is one of the best Britpop ballads ever written. Band and album are, in many ways, symbolic for the whole genre, celebrating good times you already know won’t last long.

Radiohead: The Bends

Radiohead are probably the least Britpop-like band to ever release a Britpop record. But even the Oxford oddballs could not resist the genre’s omnipresence and 1995’s The Bends tuned out to create a considerable step forward from their alt rock and grunge indebted debut Pablo Honey. When they eventually turned to Britpop, Thom Yorke & co. couldn’t help but release one of the most brilliant Britpop records ever. The Bends features hauntingly beautiful ballads like “High and Dry” and “Fake Plastic Trees,” but also outright creepy (pun not intended) cuts full of drama, doom and dread, like the surprising single and album closer “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” It says a lot it’s one of the most melancholic songs the band have ever written. In the end, though, the desperate The Bends fulfilled the dreams Radiohead had perhaps never dreamt: the album, with its magical middle-section containing “(Nice Dream),” “Just” and “My Iron Lung,” turned out to be a prelude to 1997’s OK Computer, which would secure Radiohead’s status as one of the biggest bands on the planet. While far from their most eccentric or experimental album, The Bends is the starting point of Radiohead’s startling significance.

Pulp: Different Class

Like no other, Britpop bands were able to mask their socially motivated rage with sing-along refrains. Master of that craft was Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker, one of the most cartoonish characters of the movement. After twelve long years, Pulp managed to abandon their anonymity, as they rose to fame with their 1995 masterpiece Different Class. Cocker, who formed Pulp when he was just 15 years old, soon became one of the lyrical leaders of Britpop, alternating between sexy and sharp with every new sentence. These sentences were oftentimes guided by Pulp’s soaring synthesizer melodies, which managed to sound glamorous and gritty at the very same time. Different Class, which arrived months after a last-minute Glastonbury headline set, shot the band into superstar status. The record is the first one to feature Mark Webber, the president of Pulp’s fan club, on guitar. Major hit singles like “Common People” and “Disco 2000” soon ensured Cocker & co. would never be mistaken for common people themselves again. Instead, Different Class, combining social critiques with sexual sagas and constantly contrasting its pleasure on the surface with panic on the inside, became the standout story of the underdog’s victory lap.

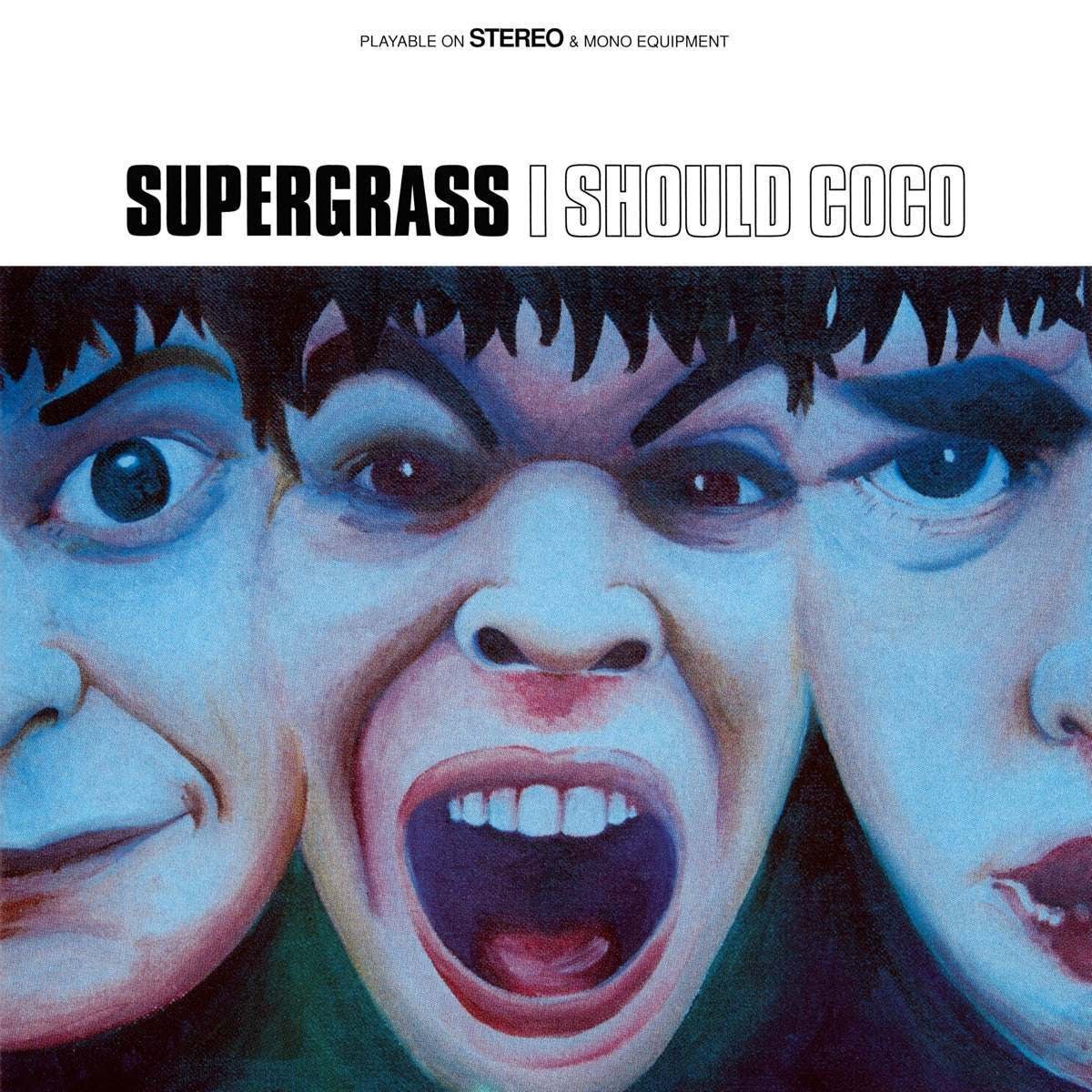

Supergrass: I Should Coco

While Britpop never was a genre known for its intricate chord progressions, Oxford band Supergrass surely belongs to the most biting Britpop bands. Everything about their 1995 debut I Should Coco, featuring their breakout hit “Alright,” is simple and speedy: most of the songs are three minutes or less and contain no more than three chords. The reckless energy reflects Supergrass’ speed of recording: the sprawling six-minute song “Sofa (Of My Lethargy)” was, for instance, recorded in just one take. The youthful vitality on the album can also be traced back to the age of the band members, who were in their teens and early twenties when they put out their first track, the semi-autobiographical “Caught by the Fuzz,” which was praised by Britpop buddies Blur and Elastica and also features on I Should Coco.

Elastica: Elastica

If there was anything Britpop bands were good at, it was allowing youngsters in Britain to forget about their daily struggles and letting them dream of something bigger, like being in a band. The one band best at that were London’s Elastica, founded by ex-Suede members Justine Frischmann and Justin Welch in 1992. When Elastica’s first LP was released in March 1995, it became the fastest-selling debut album since Oasis’ Definitely Maybe. The record, which sort of sounds like a fun version of a Wire album, is full of poppy punk songs about sex. 16 of them in 40 minutes, to be precise. Frontwoman Frischmann sure knew what she was talking about: initially a romantical partner to Suede’s Brett Anderson, she later left him for Blur’s Damon Albarn, becoming Britpop’s First Lady. In the late 90s though, Frischmann’s sweet relationship with Albarn as well as with her band mates went sour and Elastica’s second record, 2000’s The Menace, did no justice to the band that was once the very definition of Cool Brittannia.

Manic Street Preachers: Everything Must Go

While Britpop made way for new British guitar music, not all bands were gladly associated with the movement. One of those bands was Manic Street Preachers, who hated Britpop for its deigning depiction of the working classes. Against all odds though, bassist and lyricist Nicky Wire managed to mutate grief into glory shortly after the sudden disappearance and supposed death of his best friend, Manic Street Preachers guitarist Richey Edwards. 1996’s Everything Must Go, which was released a year after Edwards’ passing, features several posthumous lyrics by the guitarist, for instance on Small Black Flowers That Grow Into The Sky, a track about animals in captivity. The cleverly commercial power-pop also hides textual twinges elsewhere on the album, which contains songs on a suicidal photojournalist and an artist with Alzheimer’s. Despite its pitch-black background, the album was hailed as a masterpiece of mourning and managed to make waves in the British mainstream. It’s the remaining trio’s tear-jerking tribute to Richey Edwards and a reminder that Everything Must Go on.

The Verve: Urban Hymns

While most Britpop musicians came from fairly modest walks of life, they seem to succeed best if they temporarily confuse themselves with the messiah. The Verve’s Richard Ashcroft, the inspiration for the Noel Gallagher penned “Cast No Shadow” on Oasis’ aforementioned (What’s The Story) Morning Glory, is perhaps the best example. On his band’s magnum opus Urban Hymns, even its title hints towards the record having some sort of mass function, he starts off by letting his listeners in on the meaning of life. The weird and simultaneously wonderful thing about the Stones sampling Bittersweet Symphony and the songs that follow? Ashcroft’s unshaken self-belief makes sure there’s not a second of doubt he’s speaking the truth. It’s the fact that Ashcroft performers these lush love songs as if they were the most important songs every written that keeps them from being laughable listens and elevates them to a powerful pinnacle of a long career, as well as one of the last truly great Britpop records to ever see the light of day.

加入俱樂部!

立即加入,起價44美元Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!