É melhor queimar do que desbotar? Em seu potente e elegíaco poema "Para um atleta morrendo jovem", A.E. Housman implica que é o primeiro sentimento. A peça lamenta a morte de um corredor atingido no auge de seu poder físico, com Housman escrevendo: "Criança inteligente, que seja esperto o suficiente para escapar a tempo / Dos campos onde a glória não permanece."

Neil Young, who posited this dilemma in “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black),” agrees, though the schism in logic presented in the argument is alarmingly transparent: An apocryphal narrative is ascribed to untimely death in order to give its absurdity some deeper meaning, however, what could have been is no longer an accountable variable—or as Young sang, “once you’re gone you can never come back.”

The “live fast, die young” rock and roll narrative is pernicious—case in point, Kurt Cobain quoted Young’s line in his suicide note—but sadly, artists do die before their time and leave in their wake stunning albums, which because of or in spite of death come to define their careers. What could have come next is a great mystery and perhaps that is why the public is so fascinated by the trope.

Karen Dalton: In My Own Time

All too often an artists’ authenticity is questioned when they are an interpreter rather than a writer of songs. Karen Dalton never recorded any original material, but her second and final album In My Own Time is a compelling antidote to this flawed argument. Dalton didn’t need to write the songs that compose this album because her arrangements often transcend the originals. Listen as she transforms a second-rate ballad from The Band into a standout with soul. And then there’s her unforgettable voice, which sounds like a crumbled love note repurposed into a paper airplane gliding with grace. There’s a reason Bob Dylan called her his favorite singer.

Nick Drake: Pink Moon

With the exception of the piano solo on its title track, the entirety of Pink Moon is just Nick Drake’s voice and guitar. Eschewing the baroque strings of his previous work, Drake recorded this plaintive, acoustic album by himself in only two late night sessions. The loneliness of this album is strikingly portentous. At this point, Drake had begun withdrawing from life, barely speaking (he’s mumbling just enough to be understood on this album) and would eventually succumb to his battle with depression, committing suicide two years later. The epitaph on Drake’s tombstone is taken from Pink Moon’s final track, “From the Morning:” “And now we rise / And we are everywhere.” Rarely has such tragic beauty been captured before or since.

J Dilla: Donuts

J Dilla recorded 29 of Donuts’ 31 tracks during an extended hospital stay. The album is an influential piece of work made by someone who knew he was living on borrowed time. Donuts was released on Dilla’s 32nd birthday. Three days later he died of the incurable blood disease he was diagnosed with in 2002. Like DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing….. did 10 years earlier, J Dilla’s Donuts pushed the boundaries of instrumental hip-hop and created a soundscape the listener could live in. However, Paul’s Boutique’s sample-based snippets, courtesy of the Dust Bros., prove to be Donuts’ obvious antecedent. Dilla created an album that is at once both a collage of cut-ups and a cohesive work that flows with songs segueing seamlessly into one another. It’s a testament to Dilla’s creative voice that an album that never features his vocals could sound so much like him.

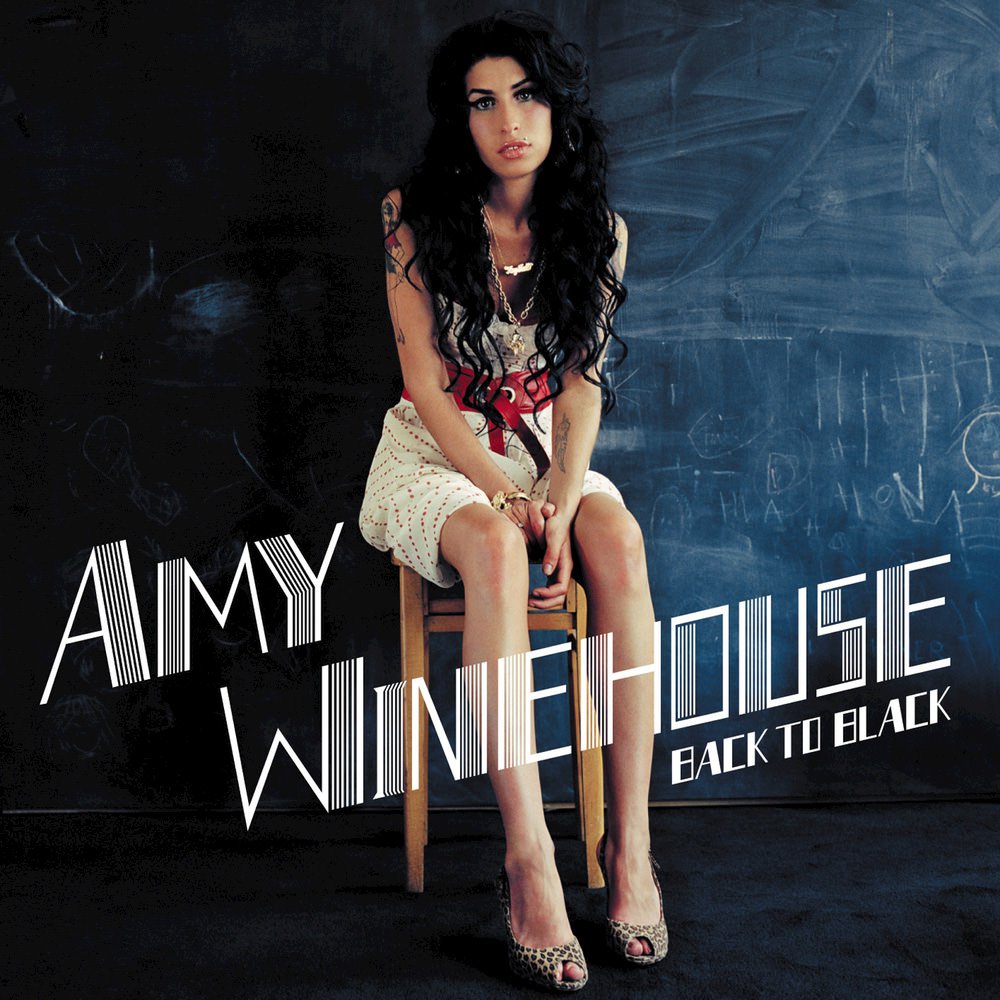

Amy Winehouse: Back to Black

Since providing production on Back to Black, most notably on hit “Rehab,” Mark Ronson has gone onto become a household name. Before her death, Amy Winehouse became a household name as well, though often spurred by the downward spiral of her personal life. A damn shame because listening to this album is an infuriating exercise in, “what if?” There’s so much talent present in Winehouse’s ballads—most of which she wrote herself. Her neo-soul sound borrows from ’60s girl groups, Brill Building songwriting, and jazz, but melds it into something new. The subject of heartbreak looms heavy on this album—especially on its title-track in which Winehouse sings, “you go back to her and I go back to black”—but Amy knows the age-old subject so well that she crafts songs that all these years later are as capable of making you sing along as they are of making you sulk in sadness.

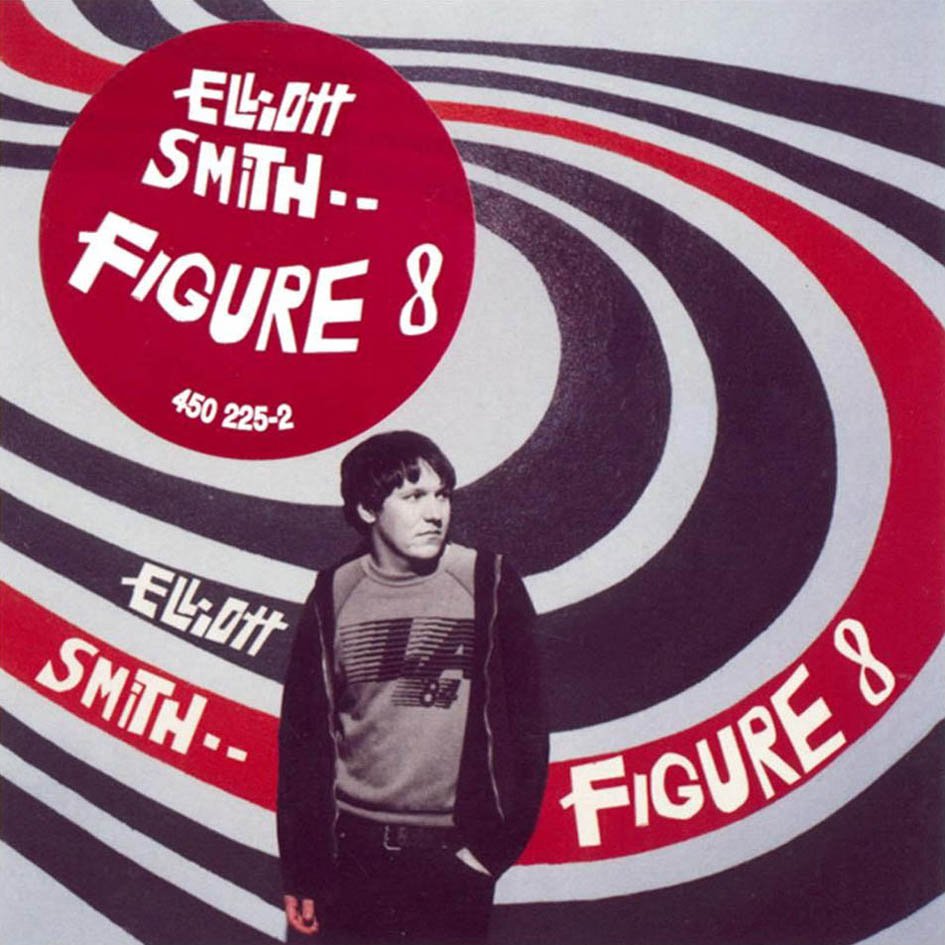

Elliott Smith: Figure 8

The one on which Elliott Smith goes big-studio much to the chagrin of some long-time fans. Smith really took advantage of his major label budget pushing the production to even higher level of grandiosity. The album sounds like if Either/Or had said, “both!” There are times when the songs sag under the weight of their arrangements, but are pulled up by their sheer ambition. Underneath the '60s pop gloss are still the ineffable elements that make up the best of Smith’s songwriting shtick with a Rolling Stone reviewer even bemoaning Smith’s propensity to be a perpetual bummer. A month after *Figure 8’*s release, Smith said “I don’t think perfection is very artful.” Maybe the album is so artful because it could never be perfect.

Notorious B.I.G.: Ready to Die

While Ready to Die was technically the only Notorious B.I.G. album to come out during his lifetime, its follow up, Life After Death, was completed and scheduled to be released two weeks after the date on which Biggie was shot four times. Life After Death brought the big guest features, but Notorious was always big enough to fill out a whole album alone as evidenced by all the classics contained on Ready to Die: the rags-to-riches saga in “Juicy,” the dance floor jam “Big Poppa,” “Gimme the Loot” on which Biggie holds his own playing two distinct characters, and the warped Muzak dirge of “Everyday Struggle.” The album also uses one of earlier examples of a rapper talking candidly about mental illness (“Suicidal Thoughts”). Biggie’s talents lie in balancing the lowest lows of the gritty struggle with over-the-top braggadocio claims of someone at their highest highs. And why not? Biggie would never be so big again.

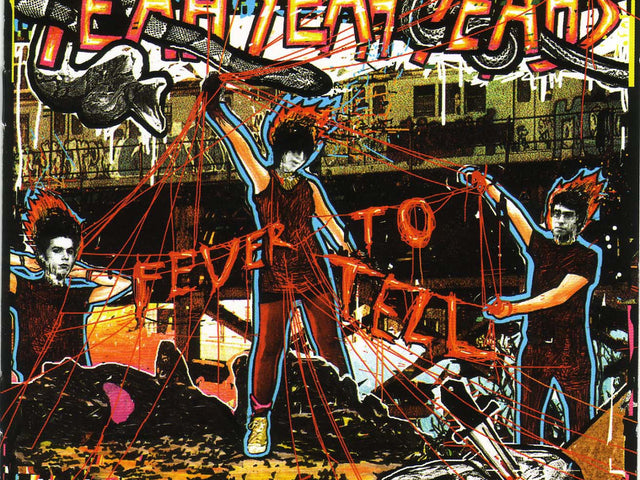

Jay Reatard: Watch Me Fall

The creative parameters for Jay Reatard’s Watch Me Fall were strikingly similar to Elliott Smith’s last effort: both artists signed to larger labels whose budgets they mined for grander production. Each created something decidedly more polished, each was the project’s sole songwriter, and each played nearly every instrument sans some limited drums and strings. Blood Visions, Reatard’s solo debut following his stint fronting the Reatards, hints at the direction Reatard would go with Watch Me Fall—there are moments that explore broader pop sounds but the album generally is rooted in Reatard’s brand of punky garage rock. The “maturing” career arc is trite, but given his prolific pace it’s hard not to imagine had he lived that this guy giving Ty Segall a good run for his money as garage rock’s premiere songwriter.

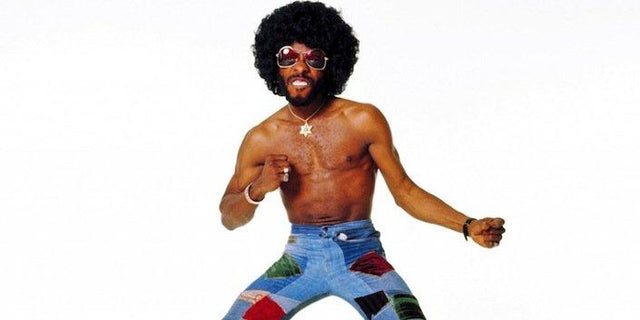

2 Pac: All Eyez on Me

Curating a roster of guest appearances is integral in separating the good hip-hop albums from the great hip-hop albums. Part of what makes My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy a masterpiece is Kanye’s MO to let other MCs shine in the spotlight. But like many hip-hop milestones, Tupac did it first (All Eyez on Me is hip-hop’s first double-disc album). All Eyez on Me is a template for how to do guest spots right. Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg, Method Man and Redman, Dr. Dre and George Clinton are welcome features alongside one of the genre’s absolute best and his best. At two hours and 12 minutes, it can drag at times—one reviewer joked that even Kendrick Lamar hadn’t heard the whole thing. But the high points are strong enough to pick up this slack and even set a new standard for how big a hip-hop album can be.

Judee Sill: Heart Food

After her mother remarried, Judee Sill, in an act of defiance, resigned to a life on the road, a move that would prove to be both the catalyst of her career as well as a catalyst for its downfall. It was during this time that her casual interest in music grew more serious but so did her dalliance in drug usage eventually leading to a heroin addiction that would take her life in 1979. Sill only released two gorgeous albums in her lifetime, the latter of which, Heart Food, is an underrated classic of the early ‘70s Laurel Canyon scene. Sill referred to her music as “country-cult baroque,” which is apt description given the melding of her two main influences, Bach and the Bible. Sill, who was a fastidiously slow songwriter, took on even more responsibility, orchestrating and arranging Heart Food making the album Sill’s most personal work.

Arthur Russell: World of Echo

Compiled from material he had written from 1980 – 1986, World of Echo is Arthur Russell in his most raw form. The release sounds like one amorphous piece fading in and out instead of 14 distinct tracks but that’s part of its charm: it floats by and while it may seem to challenge the listener, they are meant to let go and allow it it take them on a journey. Russell’s style has always been difficult to classify because he experimented with so many disparate genres. World of Echo is no exception. Is it ambient, minimalist avant-garde, krautrock? It’s a bit of all of these descriptors. Its title is the perfect summation of what the album is: Russell’s inimitable tenor sounds like it’s being broadcast from a cave on Jupiter. Shortly after World of Echo was released, Russell was diagnosed a HIV-positive. He continued to record despite developing throat cancer, but his last effort remains his most oddly satisfying.

Alex Wexelman is a freelance writer residing in Brooklyn. He has bylines at The Village Voice, Bandcamp, Brooklyn Vegan, Paste and other sites, which have graciously allowed to ramble about rock music.

Related Articles

Junte-se ao Clube!

Junte-se agora, a partir de 44 $Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!