De 10 beste moderne klassieke albums om op vinyl te bezitten

Classical muziek kan stoffig, saai en ouderwets lijken. Maar als het goed gedaan is, kan het uit je luidsprekers springen als geen andere muziek. En we hebben het niet over gedwongen luisteren naar de symfonie van een oude man in de muziekles, of die keer dat je als kind naar een saaie concert werd gesleept. We hebben het over originele muziek van levende componisten, gehoord op onberispelijke vinyl.

Why listen to modern classical? Because you need a change of mindset. It’s been a long day. You’re sitting on your hands until the next paycheck clears. You had it out with your roommate over laundry and dishes left undone. You’ve got a family thing tomorrow to go to, or a work thing you’ve been dreading. Set all that aside for a minute.

These ten albums can change the way you think, and not just about classical music. There’s experimentation, uncertainty, complexity, triumph, and pure joy. It’s a lot to take on in one sitting. But there’s no better experience than dropping the needle on music that’s so cinematic it should come with popcorn and a content advisory. It’s rare, and it’s hiding in plain sight.

Rest assured, your friends don’t know about these albums. You’ll hear old classical standards chopped and screwed into new art-music anthems, original works that eggheads and pencil-pushers haven’t even formulated misbegotten theories about. (Ignore them when they do.) You’re getting in on the ground floor. Snap these titles up on vinyl and don’t look back. It’s time we reclaimed classical music — and all these hectic days — for ourselves.

Helene Grimaud: Water (2016)

Your typical classical music audience isn’t hard to win over. Play the hits, throw some high-power names on the bill and you’re good to go. Younger audiences are harder to impress. In a culture positively drunk on good music you need an irresistible pitch to capture the audience’s attention, and a steady hand to keep the skeptics in their seats. In her latest release, pianist and millennial soothsayer Hélène Grimaud provides a blueprint for doing just this. Water Music binds together 19th-century heavyweights — Liszt, Fauré — with 20th-century contemporary tunesmiths like Debussy, Ravel and Berio. The secret here isn’t a simple old-meets-new pairing. It’s been done, nobody cares. Grimaud’s genius stroke is using composer Nitin Sawhney’s murky, portentous writing as a seamless gloss from one piece to the next. Sawhney’s music is deep and complex. Here in Grimaud’s hands it effortlessly binds Water Music together. The result is a seductive album that’s worth building into an afternoon, a restless, achingly beautiful work that stands up to repeat listens.

Uri Caine: Primal Light (1997)

Gustav Mahler’s music was punk before studded leather jackets and spray-on skinny jeans came around. Mahler was a revolutionary, drawing on sounds other composers wouldn’t dare, interpolating rustic folk tunes into epic, world-beating anthems, funneling fury and majesty into incomparable works. In the intervening years, rote orchestral performances have dimmed Mahler’s shine. But pianist Uri Caine’s Primal Light reignites it. Caine takes heavy cuts from the Mahler canon — movements from symphonies, song excerpts — and punches them up in new, sometimes jazzy chamber arrangements. Primal Light restores Mahler to his 1000-megawatt brilliance. Mahler is the man who wrote for massive ensembles — his Eighth Symphony is nicknamed “The Symphony of a Thousand” — but Uri Caine uses a crew of only 13. Power and potency are the keys. Caine’s Primal Light is fresh and surprising, making it an essential addition to your vinyl library.

Bryce Dessner + Kronos Quartet: Aheym (2013)

The National’s Bryce Dessner has grown in reputation from indie band darling to something of a contemporary classical music sensation. His collaborations with eighth blackbird resulted in the sensational Filament, an album that won Dessner and the group a Grammy Award. Dessner is a consummate collaborator who has worked with Steve Reich, Sufjan Stevens, Philip Glass, Hiroshi Sugimoto and many others. For the 2013 album Aheym Dessner enlisted the fearless, shape-shifting Kronos Quartet to play an album entirely of his own devising.

Aheym’s title track is a churning, biographical account of his Jewish immigrant grandparents’ settling in Brooklyn, premiered at the Celebrate Brooklyn! festival. Tenebre is a shadowy meditation named after the Holy Week service. Little Blue Something balances out the two with a limping groove that’s passed around, tweaked and continually reprocessed. Tour Eiffel triumphantly closes the album with an A+ feature from the Brooklyn Youth Chorus. Aheym’s runtime is a brisk 44 minutes, and Dessner and Kronos manage to say a lot in that space. It’s a great entry point for fans of The National, classical music novices, or genuine thrill seekers.

SO Percussion + Bobby Previte: Terminals(2014)

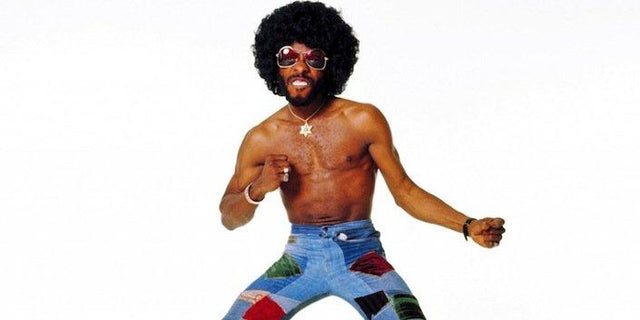

We all get a little jolt of excitement when our favorite artists team up for all-star collaborations, whether it’s Britney and Rihanna, JAY-Z and Linkin Park (kidding), or Miles and Coltrane. But the problem with a good collabo is that so much can go wrong. Players just check out, hide behind their reputations, get a little too deep into the bottle, or worse. Occasionally (read: very occasionally) things click, and their effort has a multiplier effect. The album Terminals is one such case.

Terminals features keyboardist John Medeski (Medeski, Martin & Wood), guitarist Nels Cline (Wilco), saxophonist Greg Osby (Grateful Dead, CL Smooth) and harpist Zeena Parkins (Björk, Yoko Ono) and the uber-talented collective So Percussion. Composer Bobby Previte was vexed by the indecipherable terminal maps we all encounter in airports. Rather than throw up his hands like the rest of us, Previte used them as blueprints for compositions.

While that concept sounds as dodgy as a DIY tattoo kit, Previte and company deliver the goods. Terminals is a blast. Within the strictures of Previte’s writing the musicians get loose, very loose. Nothing here is easily categorized. The group assumes and then discards different musical identities within the span of a single track. You have to keep up.

There may be more accessible classical albums out there, but this one — with its persistent experimentation both as a means to an end, and as an end unto itself — is one of the finest available.

Colin Stetson: Sorrow - Reimagining of Gorecki's 3rd Symphony (2016)

Hits are few and far between in the classical music world. Pieces like Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos don’t break through very often. Most music is played and forgotten. In 1992 Polish composer Henryk Górecki became an unlikely superstar when his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs became a runaway success. Górecki’s piece sold over a million copies, and it was doubly impressive because the work was dark and intense, the opposite of chart-topping treacle. He spun the classical world on its axis.

Wind and brass multi-instrumentalist Colin Stetson has worked with A-list musicians like Tom Waits, Laurie Anderson, Bon Iver and TV on the Radio. Stetson’s work defies easy categorization — is it avant-jazz? thumping electro? new-wave classical? — and his intersectional identity affords him a unique vantage from which to approach Górecki’s hit. Stetson’s remix of Górecki is called Sorrow, and it’s a sprawling, meditative work for a stripped-down ensemble. It holds the tension and anguish of the original — Górecki indicated each movement should be a steady, grinding “Lento” pace — with enough kick so that its power isn’t diminished.

Nils Frahm: Solo (2015)

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world it should listen to classical music to “relax.” Once that happened, the great pieces in the canon were endlessly repackaged into collections intended to be soothing and narcotic, as if the music were nothing more than the equivalent of downing Ativan with vodka and drifting into oblivion. But sometimes there’s a kernel of wisdom behind crass consumer ploys. We all need musical therapy from time to time. Enter Nils Frahm.

Nils Frahm’s Solo is music for a single piano, but if it sounds different it’s because Frahm conceived the album on a different type of piano: the Klavins M370. The M370 piano is over 12 feet tall and boasts ten-foot strings, and its superior resonance allowed Frahm the space and freedom to scratch up these eight hypnotic, improvisatory figures. Solo was first available as a web download in 2015, and Frahm has stated that proceeds from the newly-released vinyl edition will help fund an even bigger piano, the Klavins 450.

Solo lands somewhere between the Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies, James Blake’s crystalline self-titled debut, and Ghosts I-IV by Nine Inch Nails. It’s flawless escapism, and yes, you might find it a bit relaxing. There are worse things.

Max Richter: Recomposed (2014)

Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons have been recorded and performed thousands, maybe millions, of times. They’re a rite of passage for aspiring violin superstars, and a rare point of consensus between music lovers and hit-and-run listeners. That’s because they’ve been featured in movies, jewelry commercials, figure-skating routines, and even a suite of MIDI tunes included in the early Windows operating system.

Like a dope drum break in the hands of a skilled DJ (James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” anyone?), The Four Seasons have been extensively sampled and remixed. One of the latest and greatest is German-British composer Max Richter’s Recomposed. Vivaldi tends to pump scads of notes into every musical gesture. Richter and violinist Daniel Hope opted to streamline things: Vivaldi’s riffs work like guideposts that get repeatedly referenced and expanded on. A lot of material is just stripped away.

For those familiar with The Four Seasons, Richter’s undertaking may mess with you a bit. Expected arrivals never quite get there. A relatively unremarkable section gets some extra love with each emphatic repetition. Recomposed is the rare project that revitalizes the original while also asserting its own identity. It’s the ultimate homage, and one with serious staying power.

Steve Reich: Four Organs / Phase Patterns (2016 reissue)

Steve Reich is the master of minimalism, the sage of simplicity. Hearing even one Reich piece is sufficient to understanding the composer’s m.o. In pieces like Clapping Music and Four Trains Reich uses modest resources, near-imperceptible change and the passage of time to nudge listeners along. Reich’s work is spare and efficient, and while he’s never had the type of commercial success of flashier composers, he’s certainly inspired his share of them.

Four Organs / Phase Patterns was a 1971 release that perfectly encapsulated the composer’s ethic. Four Organs is, sensibly, a piece featuring four Farfisa organs being struck at intervals. These intervals change over time, of course, so that notes cross and uncross, drift and draw back together. A pair of maracas serves as the unlikely timekeeper. Phase Patterns uses a similar tactic. Organ rhythms briefly interlock before speeding up or slowing, but in this one nobody keeps the beat. This is heady, devilish stuff, the kind you find yourself wanting to hear more of.

Forty-five years is an eternity in the musical world, but this vinyl reissue of Four Organs / Phase Patterns feels as fresh as the day it was first pressed to wax. We’ll be saying the same thing in another 45 years.

David Lynch & Marek Zebrowski: Polish Night Music (2015)

Director David Lynch shocked the world in 2014 by announcing the return of his influential TV series Twin Peaks. The show morphed from a cult favorite to bona fide classic in its two-year run. Excepting an ill-conceived movie spinoff (let’s never speak of this again) Twin Peaks will be forever held in high regard by critics and Lynch fanatics alike.

Lynch-a-maniacs will be especially pleased with Polish Night Music, a Lynch joint just out on vinyl. The director has always had an ear for music — whether teaming up with composer and kindred spirit Angelo Badalamenti, or channeling Roy Orbison in a surreal scene from Blue Velvet. Polish Night Music, a collaboration with pianist and composer Marek Zebrowski, is an on-brand thriller and a worthy tide-over.

Polish Night Music began after Zebrowski worked as a translator on Lynch’s Inland Empire. The two discovered a shared musical aesthetic, and this album is an outgrowth of that. It’s only four tracks — all entitled Night with other parenthetical descriptors — and the mood is as mysterious and beguiling as the best Lynch films. Zebrowski’s playing is a slow menace, and the writing here offers more questions than answers. But if you’re a Lynch fan that’s exactly what you signed up for.

Ólafur Arnalds + Alice Sara Ott: The Chopin Project (2015)

Piano wunderkind Glenn Gould famously retired from the concert hall because he preferred the refinement and the exactitude of studio machinery. On The Chopin Project, composer Ólafur Arnalds and pianist Alice Sara Ott took the opposite approach. Instead of recording in a hermetically-sealed, meticulous studio environment, the two went gloriously rough-and-ready, recording in bars and airy, ambient rooms on well-worn pianos.

The Chopin Project requires the performer to walk a tight line, and Alice Sara Ott manages it with ease. She is fearless. Ott has the chops to make the music sizzle, and the finesse to let softer statements speak for themselves. Alongside Ott’s playing, synthesizer and strings form a worthy complement.

Sometimes the technical wizardry required for Chopin can overwhelm listeners. But Arnalds uses deft strategy to make The Chopin Project a winner. You don’t get Chopin from the windows to the wall. His music is an accent, a dash of color. Arnalds’ own compositions are featured just as prominently. The strings and environmental noise (like whispers and papers swishing) offer further breadth.

The ideas Arnalds and Ott explore here are so good that a lot is left unsaid. With any luck this is only the beginning of a recording partnership that will last for many more iterations.

Word lid van de club!

Word nu lid, vanaf 44 $Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!