Searching For Otis Redding

On The 50th Anniversary Of His Death, An Exploration Of The Biggest Question Mark In Music History

Two blocks from the Wisconsin state capitol building, and 150-odd feet away from Lake Monona-- an eight square mile lake that, along with neighboring Lake Mendota, creates the isthmus that forms the downtown of the city of Madison--is the Monona Terrace Convention Center. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the Monona Terrace Convention Center has two matching, four story pillars as its anchors, each of which features a beautifully maintained rooftop garden. On the northern pillar--near where you can enjoy a $6.95 plate of snap peas from the Lake Vista Cafe-- are three benches, centered around a solitary plaque that begins “Otis Redding: King of the Soul Singers.”

The plaque is easy to miss--its seating area is obscured by planters surrounding the dining area for the snap pea place--but it stands as the only public marking in recognition of the tragedy that happened 50 years ago today. On December 10, 1967, Otis Redding and his backing band, the mostly teenage Bar-Kays, were on their way to play a show at the Factory-- a long-gone rock club in the narrow stretch between downtown Madison and the campus of UW-Madison that is now a feminist bookstore--when their plane went down in Lake Monona. Seven of the eight passengers died, with Bar-Kays trumpeter Ben Cauley as the lone survivor. The plaque at Monona Terrace has a sad bit of trivia: the only scheduled show Otis Redding missed in his career was his show at the Factory.

The plaque memorializing Otis Redding on Monona Terrace. Amileah Sutliff

The plaque memorializing Otis Redding on Monona Terrace. Amileah Sutliff

While the plaque’s inauspicious placement on a rooftop garden that’s inaccessible for five months of the year might seem like an uninspired tribute, Redding never actually played in Madison. His shows at the Factory--one early, one late, both with the band that eventually became Cheap Trick set to open--were to be his first in the city. His connection to the city is tenuous at best, a matter of trivia and tragedy more than anything else.

That plaque underscores the reality of Otis Redding in 2017 though; it’s hard not to see him as an assemblage of numbers and cold hard facts. It’s impossible to know much of his motivations, or what he was thinking, because he was the only member of the ‘60s pop Mt. Rushmore to not have been exhaustively covered by the rock journalism infrastructure. He died before he could become canonized on dorm room posters as a member of the 27 club (he was only 26), and his death left him as the biggest what if? in the history of musician deaths; he never got to make his true masterpiece, because he was only getting started. He died seven months after his major crossover moment, and literal days after recording his biggest single.

Otis Redding is maybe the least “knowable” of all of the canonical greats in American music history. When Otis died, his story was still being written, his musical greatness just being realized, and his great statement was right there to be made. No other musical artist who died young is a bigger question mark than Otis Redding. He’s JFK, he’s Len Bias, he’s Bo Jackson. He’s a symbol of potential; of immense greatness only partially realized.

The plaque and seating area around the Otis Redding plaque. Amileah Sutliff

The plaque and seating area around the Otis Redding plaque. Amileah Sutliff

The poster for Otis' missed show in Madison. It sells for hundreds of dollars.

The poster for Otis' missed show in Madison. It sells for hundreds of dollars.

Otis Redding was born in Macon, Georgia, on September 9, 1941. Macon is located near the center of Georgia, and today has a population of around 150,000 people. Despite being unremarkable, it was somehow the birthplace for three pillars of soul and rock ‘n’ roll--Little Richard, Otis Redding, and James Brown-- and the Allman Brothers of the Allman Brothers Band.

Redding’s career started early. As a 19-year-old, he joined guitarist Johnny Jenkins’ band the Pinetoppers as a singer. The band toured the Chitlin Circuit, and Jenkins had a small, but devoted audience. In 1962, Redding drove Jenkins to Memphis, where the older singer had scored a recording date at Stax Studios, a nascent label taking on a variety of soul and R&B clients across the south in an effort to throw a bunch of singles and singers at the wall and see what stuck. Jenkins spent the better part of a day trying to record a couple songs, and didn’t do so well in that endeavor--most of the Stax house band (including Booker T. and the M.G.’s, and the Memphis Horns) begged off for the day by the time he finished, knowing there wasn’t a hit present. When there was time left on the session, someone--and reports vary on this, though apparently Redding may have asked for himself--suggested letting Jenkins’ driver cut a record. After failing as bad as Jenkins while trying to record a cover--the band members that stayed remember being furious enough to want to leave themselves-- Redding sang his “These Arms of Mine,” and the rest was history. The band and label boss Jim Stewart loved the song, released the single, and off Redding went.

His recording career only lasted 62 months, from October 1962 when he recorded “These Arms of Mine,” to December 1967. Here’s the math: Redding released five solo albums, one duets album, one live album, and 79 songs before his plane went down in Lake Monona. Four posthumous albums with 46 more songs followed over the next 31 months. Various compilations, live albums, rarities, and alternate takes have been unearthed since, but for all intents and purposes, that’s Otis Redding’s body of work. 11 albums, 125 songs in 62 months.

The most famous of those songs is by far-and-away “(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay,” a song recorded in the studio three days before Redding died. It’s almost too on the nose, a too perfect swan song; a singer writes his career defining single, his own “A Change Is Gonna Come” or “Blowin’ In The Wind,” about worrying that the social change the ‘60s was seemingly bringing wouldn’t go far enough and help everyone, only to die in a plane crash before it was released. But that isn’t the whole story: Redding never considered the song “done;” he was worried it was too poppy, was considering adding the Staples Singers as backing vocalists, and hadn’t even properly recorded the now famous outro, which might have just been a placeholder until Redding could add another verse.

A promo shot of Otis Redding.

A promo shot of Otis Redding.

Unlike every other famous ‘60s musician who died too young--from Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin to Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon--Otis Redding had only one in-depth interview before he died. That interview in Hit Parader amounts to what is essentially his only publicly articulated personal thoughts on his music, and it was a single page in a forgotten magazine. The music media was in nascent form then--Rolling Stone had started only briefly before Otis’ death--and the music media that existed at the time focused on the white boys playing approximations of 10 to 30-year-old music. Meanwhile, Otis was cutting records that pushed soul further than his idol, Sam Cooke, did, and he was touring heavily to packed houses. But unlike how every interaction Brian Jones had with a person in the last year of his life is practically mapped down to the second, no one was asking to ride Redding’s bus or chronicling his every move; he was so undocumented that there are hardly any color photographs of him in existence.

All of this isn’t necessarily a good or a bad thing; it’s all to say that the vision we all have of Otis Redding in 2017 is present solely through our relationship with his music, and, if you dig deeper, performance footage of him at 1967’s Monterey Pop festival. At best, every other piece of information--about how Redding felt, about what he was like, about what he did in his spare time--is second hand. And you get the sense that even the people who were close to him--Steve Cropper, who co-wrote “(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay,” Booker T., members of the Bar-Kays--didn’t completely understand what made him tick either. Their recollections are mostly colored with the passage of time; they loved Otis, he was great, always quick with a joke, and though he was a tomcat, he loved his wife Zelma.

Despite being mostly biographical conjecture with regards to the motives, feelings, and thoughts of Otis himself, there are a number of amazing books on Redding (and a number of others that have drawn lawsuits from his estate). Mark Ribowsky’s Dreams to Remember: Otis Redding, Stax Records, And The Transformation Of Southern Soul is a straight ahead telling of Otis’ life, which features a fairly comprehensive blow-by-blow of Redding’s fateful last plane ride, and the aftermath following it. Jonathan Gould’s Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life, however, is probably one of the best music biographies out; it places Redding in his historical context of the morphing of gospel into soul music, and has in-depth discussions of studio sessions and tour dates.

But even Gould knows he doesn’t have the full story. He notes in the intro that hardly anyone knew much about Redding’s life story when he died in 1967. And nothing can change that; no amount of historical context or quotes from former bandmates will get you as close to Otis Redding as the feeling you get in your chest during his opening verse of “Cigarettes and Coffee.”

In the summer of 1967, promoter Lou Adler and Mamas and the Papas member John Phillips had the radical idea to stage a concert at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California. This was before Woodstock, and before bands like Led Zeppelin were touring hockey arenas; the gigantic American festival infrastructure was more or less invented in order to pull off Monterey Pop Festival. Tickets ranged from $3 to $6.50, somewhere between 25,000 and 90,000 people came each day, and the lineup was meant to reflect a who’s who of young-people popular music: the Who--making their most major U.S. performance to date-- Jefferson Airplane (technically “the draw” of the fest), the Grateful Dead, and the Mamas and the Papas. But three artists more or less made their careers at Monterey Pop: Jimi Hendrix--who memorably lit his guitar on fire and publicly executed every hotshot guitarist on earth--Janis Joplin, and Redding--who closed out the fest’s second night, reportedly because some of the Airplane had seen him and didn’t want to try to follow him. And what’s more, Redding didn’t even want to perform at Monterey Pop.

In 1967, Redding was making bank touring America, and had even started nurturing young artists on his own label. He successfully helped launch Arthur Conley, and was rumored to be a target for Atlantic Records, who would seek to to buy him out of his Stax contract and make him a mega star with their major dollars behind him. So, when his manager came to tell him he wanted him to play a pop festival with a bunch of white rock bands, and, furthermore, expected Redding to do it for free--like the other bands on the bill--he was reluctant. But the opportunity to perform to a crowd that was different than the typical one packing out his club dates was too good an opportunity to pass up.

Watching video of the performance--released as part of Criterion Collection’s release of the documentary on Monterey Pop--is like watching video of Picasso painting Guernica, of Wilt Chamberlain scoring 101 points, of Shakespeare putting his pen down on the final edit of Hamlet. It’s his live masterpiece. He comes out and says “This is the love crowd, right?” and then goes into a straight take of “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” before stopping and starting it in the middle; he has them eating out of his hand. He then did a soulful take of “Satisfaction.” You can’t watch the sweat fly off of Redding during this performance and not want to own every album and single, and not want to follow him into war.

Monterey was the first move in Redding’s push on the mainstream; it got him written up in mainstream publications, and noticed by a rock crowd that was only then allowing itself to be won over by soul music. But his transition to a mainstream star was one that wasn’t completed until his plane crash.

There’s a probably apocryphal story that after Monterey Pop, Redding needed to take some time off to get throat surgery and spent his convalescence trying not to talk and trying not to go crazy with boredom. He opted to spend most of his time catching up on popular music, repeatedly listening to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, attempting to dissect it. Redding knew that he raised the ante, and that his competition was no longer just Sam and Dave; he was boxing with the acts popular amongst the white kids in Monterey.

The vision of Otis Redding--by then, already the King of Soul--sitting at a turntable trying to get to the bottom of “A Day In The Life” seems like something invented for a biopic, but also feels more revealing than any possible interview ever could have been.

The outside of the Stax museum, constructed to look like it did when Otis was alive. Andrew Winistorfer

The outside of the Stax museum, constructed to look like it did when Otis was alive. Andrew Winistorfer

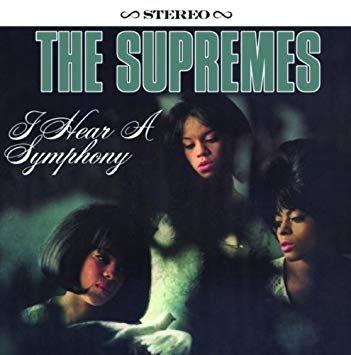

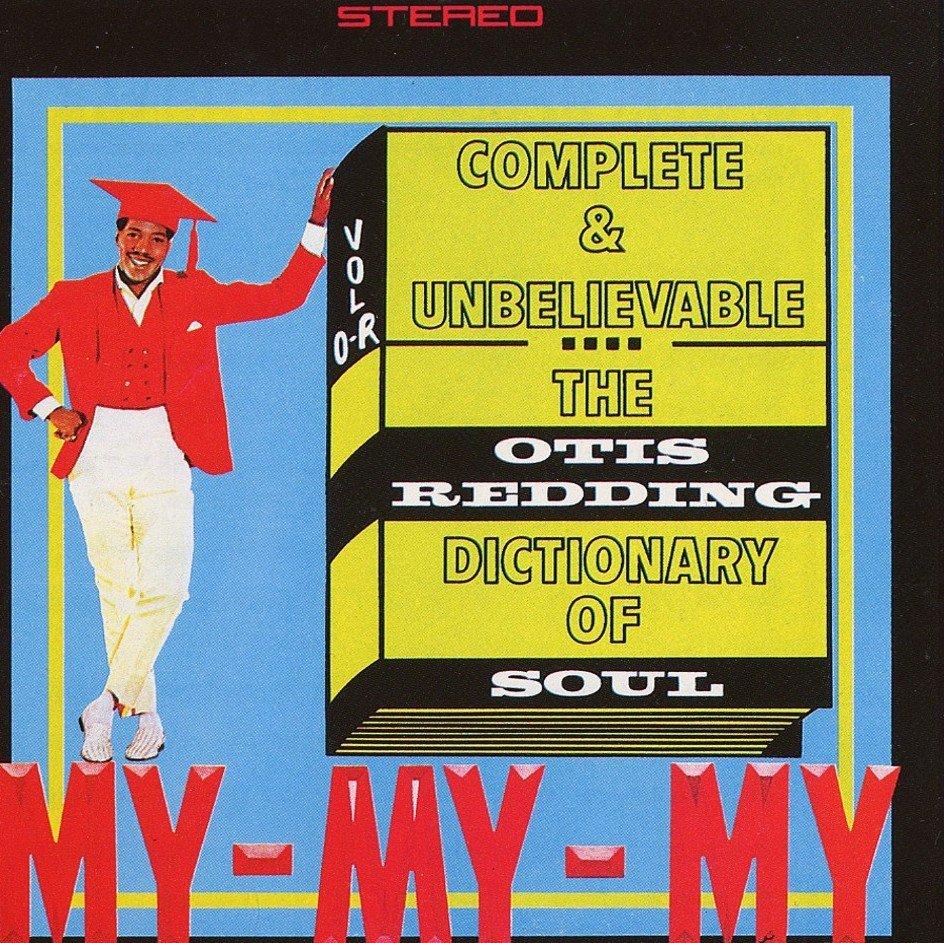

A collection of Otis Redding's albums at Stax Museum. Andrew Winistorfer

A collection of Otis Redding's albums at Stax Museum. Andrew Winistorfer

Despite being very close to the rapidly gentrifying Cooper-Young neighborhood, the neighborhood around the Stax building at 926 E. McLemore Avenue looks a lot like what it probably did when Redding and Jenkins pulled up to Stax in 1962.

There are vacant buildings and the husks of old chicken joints, and then, suddenly, the Stax Museum of American Soul Music complex. The old facade of the Stax theater looks the same, but the building is entirely new; it got razed in 1989, after Stax went bankrupt and closed in 1976. It was rebuilt in its current form and opened in 2003.

The museum sets itself apart from two other musical tourism museums in town--Graceland and Sun Studios--in that they are not monoliths just to the power of an individual or a couple of people who happened to record there. The Stax Museum aims to tell a complete history of soul music, starting with an exhibit on music in black churches, before transitioning to Sam Cooke, and basically every significant black R&B or soul star of the 20th century. See Ike and Tina’s stage outfits! See ephemera from Ray Charles!

The Stax exhibit of the museum is the biggest section though--there are impressive rooms featuring every album cover and every 7-inch the label ever put out, and a room with Isaac Hayes’ car in it--but the museum establishes that soul music was a movement, and Stax was a big part of making that movement happen.

The Otis Redding exhibit at the Stax Museum Andrew Winistorfer

The Otis Redding exhibit at the Stax Museum Andrew Winistorfer

Otis' selective service card. Andrew Winistorfer

Otis' selective service card. Andrew Winistorfer

Handwritten lyrics for "Lovin' By the Pound" Andrew Winistorfer

Handwritten lyrics for "Lovin' By the Pound" Andrew Winistorfer

The Otis Redding exhibit is small, owing, you’d imagine, to the fact that he wasn’t a mega star until after he died. In a glass case, there are some singles, an outfit he wore on tour, his Selective Service card, some candid photos, some handwritten lyrics (for “Loving By The Pound”), and a TV playing video from some of his performances.

The exhibit is the biggest what-if section of the whole museum. No one really knows what kind of heights Redding would have reached had he had lived. The Dock Of The Bay was his most complete album, and eventually his best selling. The presentation of the Redding exhibit just underlines the vast opportunities Redding had when he died. Stax might have been as big as Motown; or, at least held onto their contract with Atlantic, which was absolved shortly after Redding died and ultimately led to the label’s demise a few years later. The Stax Museum might have even been standing in its original building; not a rebuilt facsimile. His exhibit is incomplete because his life was.

The video introduction played at the beginning of the museum says “Stax isn’t in the brick and mortar; it’s in the people.” That’s true, but maybe Redding was the person who could have kept the brick and mortar together.

It was a cold and foggy day in Cleveland, on December 10, 1967. Redding and his band had played some shows at a club called Leo’s Casino the night before, and despite freezing rain across the Midwest, they never missed shows, so Redding and his band piled into the plane and headed to Madison, where they were due that night. One of the band members always rode commercial since Redding’s plane only sat eight. He would find out about the crash at the Cleveland airport.

Around 3:25 p.m., four miles out from the Madison airport at Truax Field, the pilot radioed in to ask for permission to land. Sometime after that call, the plane came out of the clouds, and crashed into Lake Monona. Some residents living around the lake later claimed to have seen or heard the plane come in close to the ground. Police made it out to the wreckage relatively quickly; they were able to find trumpeter Ben Cauley--who couldn’t swim--shivering and holding onto a seat cushion. Police couldn’t search much that first day, because the water was so cold. They resumed their search after the sun came up on the 11th. They found the other seven passengers during that morning.

Otis Redding was officially pronounced dead on December 11, 1967. His funeral was a week later, in Macon. Jerry Wexler, the Atlantic Records executive who was grooming Otis to become Atlantic's next big star, gave the eulogy.

"Otis Redding was a natural prince," Wexler said, according to Gould's book. "When you were with him, he communicated love and a tremendous faith in human possibility, a promise that great and happy events were coming."

“(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” would be released as a single less than a month later. It was Redding’s only number one hit.

Andrew Winistorfer is Senior Director of Music and Editorial at Vinyl Me, Please, and a writer and editor of their books, 100 Albums You Need in Your Collection and The Best Record Stores in the United States. He’s written Listening Notes for more than 30 VMP releases, co-produced multiple VMP Anthologies, and executive produced the VMP Anthologies The Story of Vanguard, The Story of Willie Nelson, Miles Davis: The Electric Years and The Story of Waylon Jennings. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $36Pages