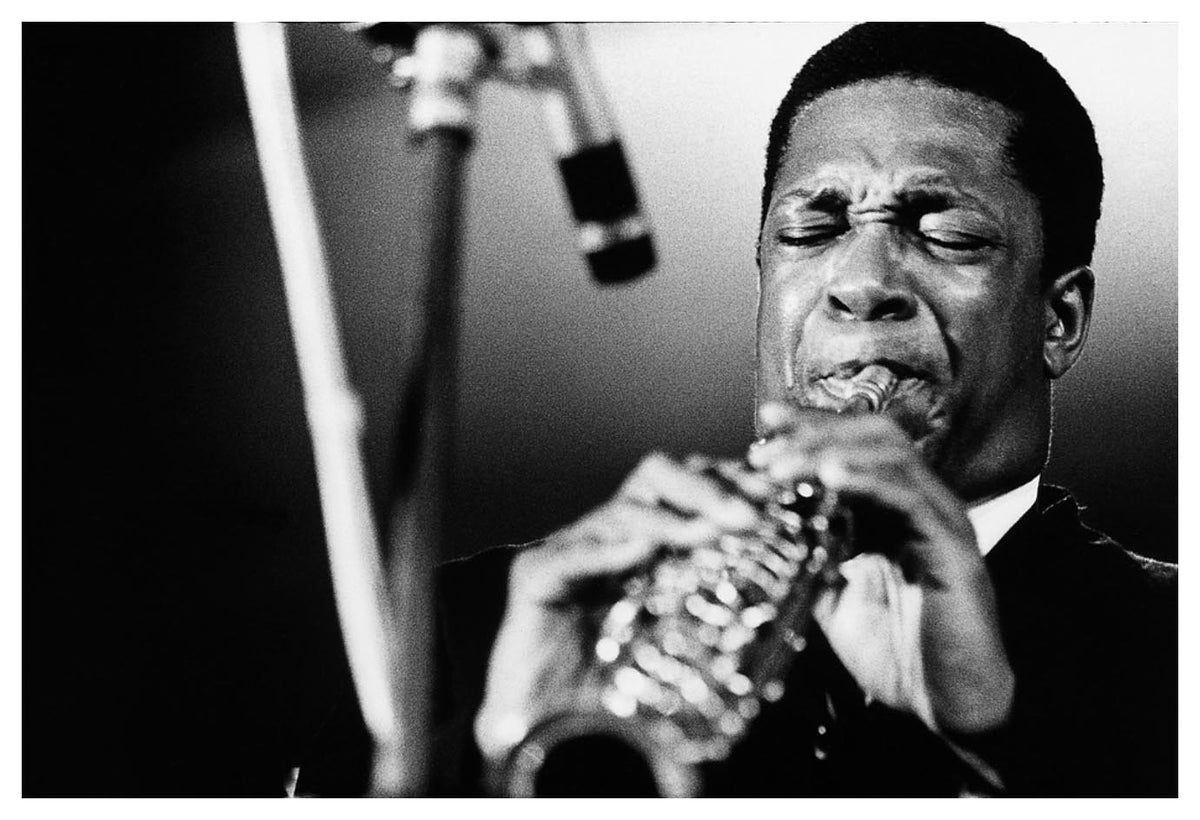

As with other popular genres, it helps in jazz to have solid commercial footing before getting experimental. Miles Davis dropped Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time, before throwing in electric guitars for his 1970 classic Bitches Brew. John Coltrane not only played on Kind of Blue, but also had a couple of best sellers of his own — he could afford to cavort with Middle Eastern influences. Avant-garde jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor had to wait a little bit before he got his roses as he was breaking ground. His complex style made it increasingly difficult to find work. “I was washing dishes in a restaurant at the same time I was being written about in places like DownBeat,” he told Downbeat in 1990. “And it was very good for me, because I had to decide what I really wanted to do. Did I want to pursue my ideals badly enough? It was the only way to learn that I did.”

Taylor won the MacArthur Fellowship the year after that interview ran and won the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship two decades before, so it’s not like Taylor’s genius has gone unnoticed. But perhaps what’s kept him from common music lexicon is how he doesn’t really care for making that genius accessible. At the center of his legend is his rejection of basic jazz concepts and structures, a worldview that guided his 1966 masterpieces Unit Structures and Conquistadors! He didn’t quite disdain traditionalism — in fact, he’s spoken about his appreciation for European constructs before. But he believed they were just as valid disassembled and remixed. “You see, what white intellectuals must be confronted with is the black methodology that creates this music,” he said to Jazz & Pop Music in 1971. “Stravinsky and Bartók made a statement in a certain way, but blacks put it together differently — their way.”

By the time he died on April 5, plenty of other listeners willing to lean into Taylor’s tangled sonics discovered the same. Here are the essentials for one of jazz’s most innovative minds:

Jazz Advance (1956)

Taylor’s first ever album sounds conventional compared to his later stuff for a fairly obvious reason: Four of the seven tracks are jazz standards, two of them coming from genre legends Thelonious Monk (“Bemsha Swing”) and key inspiration Duke Ellington (“Azure”). But Jazz Advance isn’t so traditional that it doesn’t show hints of his signature avant-garde approach. Moments like drummer Denis Charles’ maddened stomps on Taylor original “Charge ‘Em Blues” hint at the fury that’d take hold of even his future bands’ more obtuse performances. Even fairly straightforward standards like “You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To” are here to get deconstructed and remolded on the canvas of Taylor’s piano. Things would get weirder (and better from here).

Looking Ahead!/Excursion on a Wobbly Rail (1959)

Looking Ahead! still finds Taylor in the more accessible phase of his career, though his sounds are a bit more whimsical than Jazz Advance. Taylor’s solo outbursts aren’t as absurd as it would get in the ’60s, but there was little doubt he was a virtuoso. His skills are just at their most palatable here, especially on Looking Ahead’s long cut “Excursion on a Wobbly Rail.” Taylor would take the album’s bassist Buell Neidlinger and drummer Denis Charles into stranger territories by the early ’60s.

The World of Cecil Taylor (1960)

Coming right after his more conventional late ’50s period and at the start of the experimental ’60s, The World of Cecil Taylor stands as the easiest entry point for out-there Cecil Taylor. While the Unit — the Taylor band behind his 1966 opus Unit Structures — thrives on a more kinetic dynamic, World’s quartet composes a more stable soundbed for Taylor to go to work. The project is a showcase of Taylor’s adventurousness and control; his ecstatic runs on “E.B.” feel just as significant as the sustained notes that deliver its emotional closure. The quartet also features a 20-something future legend, Archie Shepp, whose sax steals the show on World closer “Lazy Afternoon.” A Shepp/Taylor collaboration shouldn’t be too hard of a sell.

Unit Structures (1966)

It’s easy to fall into paroxysms and hyperbole when speaking of free jazz: How do you define something that’s pridefully definition-less? Unit Structures stands as Taylor’s opus as well as the genre’s high mark, yet you don’t fully engage with its truth through heady terminology. Yes, it’s an uncompromisingly complex listen, but the magic lies in how every strand of fury feels palpable. Recorded during Taylor’s Blue Note stint, the septet of Taylor, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons; oboist/clarinetist Ken McIntyre; bassists Henry Grimes and Alan Silva; and drummer Andrew Cyrille put together a record of unpredictable kismet — like throwing jigsaw puzzles at the wall and it magically landed completed on the floor. This happens with each instrument carrying their distinct personality: The bass’ contained violence juxtaposes Taylor’s dizzying performance. Still, every note feels liberated in this space.

Conquistador! (1966)

Conquistador!, the second of Cecil Taylor’s two 1966 Blue Note albums, swerves away from Unit Structures’ fire and evokes the coolness of its cover, which features a turtlenecked Taylor slightly out of focus, hiding behind shades as he mysteriously stares into the distance. The musical elements don’t combust as much as they melt into each other: Horns swell shrilly at the borders to add haunted textures, while Andrew Cyrille’s amorphous rhythms tie the masterwork together. Even without Unit Structures as its contrast, Conquistador! still stands as a great testament to this sui generis collective.

Student Studies (1973)

As you may have noticed, Cecil Taylor was on point in 1966. Another example of his on-ness is this November 30 performance in Paris that finally saw a release seven years later. More Conquistador! than Unit Structures, Student Studies is another example of how well of a match Taylor found in alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons and drummer Andrew Cyrille, who backed both of those prior efforts. It’s not just that they’re both exceptional musicians — they both adroitly engage with even Taylor’s wildest piano blitzes. Lyons’ sax rises to evoke whatever tension is left in the space between Taylor’s notes, and Cyrille’s frenetic rhythms sinew the eccentrics.

Silent Tongues (1974)

Assaultive yet nuanced, Silent Tongues is perhaps the biggest testament to Cecil Taylor’s genius as a musician. There’s a thrill in hearing Taylor’s avant-garde ideas unmoor themselves alongside other musicians, but this solo performance at recorded at the 1974 Montreux Jazz Festival shines because of the sheer breadth of his musical language. He feels improvisational without feeling purposeless: The mile-a-minute stream of notes are tethered to the drama of his percussive slams and even the shards of familiar blues riffs feel renewed and distinct here. In all, Silent Tongues is what we speak of when talk about the expansive possibilities of 88 keys.

You can buy a newly reissued, exclusive variant of this album right here.

Cecil Taylor Unit (1978)

Though Conquistadors! was a career highlight, it wasn’t until 12 years later until Taylor took his band to a recording studio to cut another album. Boldly, he came back at almost 50 years old with a particularly challenging listen in Cecil Taylor Unit. Taylor has always been open about his appreciation for European and orchestral musical concepts, and it’s here we hear him stretch that influence into extreme lengths where brass and violins screech in calamity. Cecil Taylor Unit is intense, but it does offer its rewards — the dramatic swells of “Serdab” being one of them.

3 Phasis (1978)

Birthed from the same sessions that delivered Cecil Taylor Unit, 3 Phasis almost completely abandons the sense of cool in Conquistador! for a 57-minute composition that flips between imposition and a constant threat of implosion. Moments like the violent orchestral swells in part three and the haunted, discordant piano thud that closes the album stands as some of his catalog’s most thrilling moments.

Brian Josephs is a culture writer living in Brooklyn. He's been seen on SPIN, Complex, Pitchfork and more. He accepts payment in U.S. dollars and rice grains.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $36Pages