Johnny Cash And His Prison Comeback

Read The Liner Notes For The First-Ever VMP Country Release

Sometime in 1878, a construction worker laid the first stone for what would be one of the most brutal institutions of the American Carceral State and the recording locale of the most important country album to be committed to tape. Located along the American River, some 20-odd miles from downtown Sacramento, California, Folsom State Prison was completed in 1880, and from the beginning, was created to house convicts without much regard for their personhood. They were put behind steel doors, and in cells with no natural light, left to rot in darkness and wonder what they could have done differently.

Meant to house 1,800 inmates, but often housing more, Folsom was known in the penal system for its poor food and water quality and the brutality of its guards and environs. Folsom eventually got lights — it was the first prison in the entire world to have electricity — but its reputation as the most feared lasted until at least the 1930s, when Alcatraz surpassed it in notoriety. But Folsom, the second-oldest prison in California, opened 30 years after the state was accepted into the U.S., retained its ability to break men down to nothing.

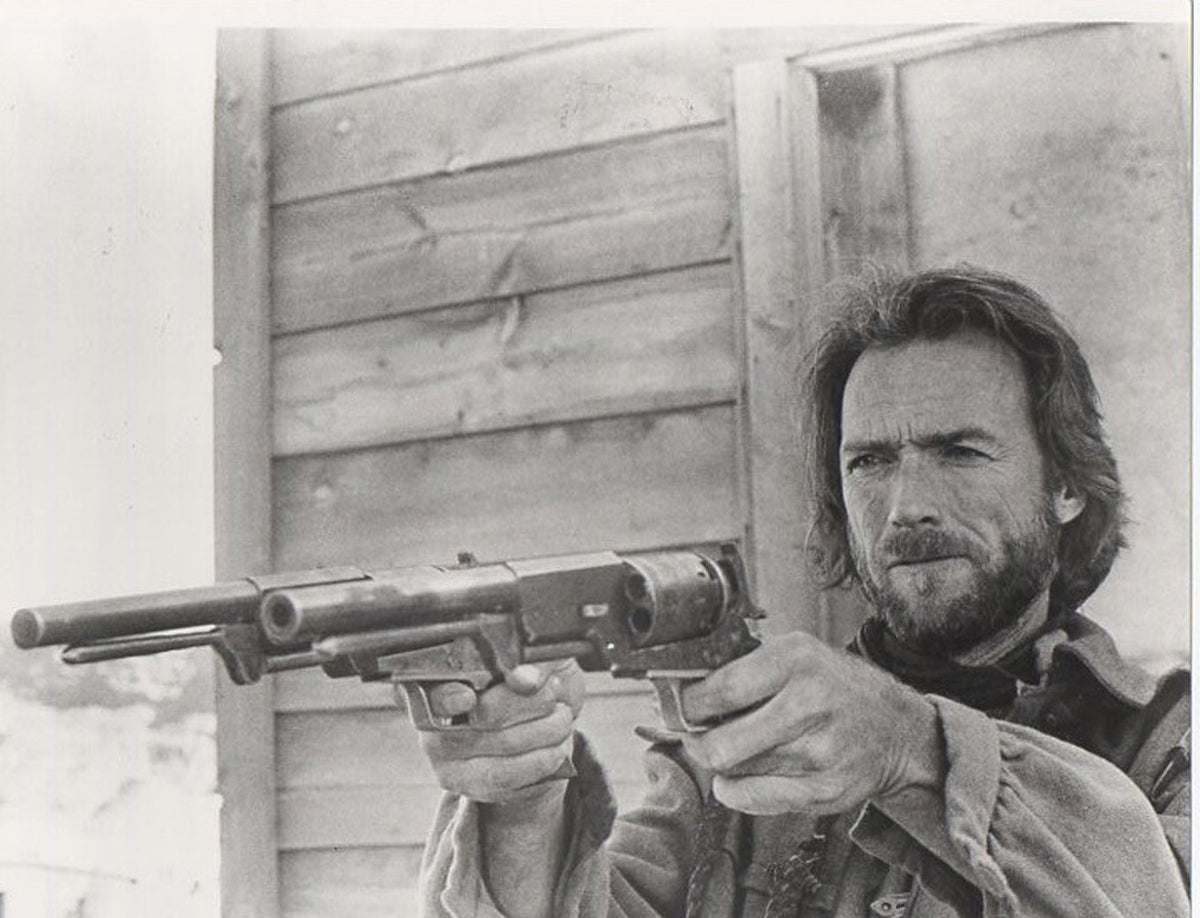

So, imagine: You’re an inmate in January, 1968. You’ve eaten your inedible breakfast and drank your gray glass of water. You’re then invited to a rare occurrence: You have entertainment this morning. You get to sit in the cafeteria, on benches that have been bolted to the floor to prevent a riot, to hear a singer. That singer comes out, introduces himself, and proceeds to deliver a set heavy on songs you can relate to. He sings about swinging from the gallows, sings about writing letters home to Mom, sings about doing cocaine and raising a ruckus, sings about shooting a man in Reno just to watch him die. Hell, he even sings about being locked up in Folsom, and performs a song by some guy a cellblock over.

This singer had never actually done time, but he does what no one else does to you: He treats you like a man, like a person. He cracks lame jokes, he swears for a cheap pop, and he seems to actually understand what you’re going through, the type of longing, dread, and inertia that makes prison life awful and terrifying.

There would be many, many myths written about what you got to see that day, but there would be one incontrovertible fact when you went back to your cell: Johnny Cash walked into Folsom Prison and tore that fucker down.

It’s hard to square the Johnny Cash who existed before At Folsom Prison and after, and that might be the album’s greatest feat, ultimately. It made Cash into the Man in Black, the iconoclast whose middle finger gestures to the establishment have been on dorm room walls for time immemorial. But it’s important to remember this when considering At Folsom Prison: The album was a total fluke, a No. 1 hit that happened only when Cash bottomed out and his label finally agreed to record one of the prison shows he’d been doing for more than a decade. “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose,” said a country songwriter not long after.

The idea of performing in Folsom Prison really began a decade and a half earlier than when At Folsom Prison was recorded. Cash, a United States Air Force serviceman in 1953, was stationed in Europe, which meant during the Cold War he mostly hung out watching movies and trying to intercept telegraphs and Morse Code coming out from behind the Iron Curtain. Sometime in 1953, around when he was — and this is true — the first American citizen to learn of Joseph Stalin’s death via a communiqué he intercepted, Cash watched the noir film Inside The Walls of Folsom Prison, a frothy 1951 movie that has as its central argument/plot device a battle between rehabilitation and harder punishment that ends unpredictably. The film spurred Cash — then a budding songwriter with a dour baritone he was growing into — to write “Folsom Prison Blues,” a song from the perspective of a murderer watching the world pass him by on a train from inside his cell at Folsom.

When Cash got out of the service, he moved to Memphis, linked up with Sam Phillips and Sun Records, and recorded “Folsom Prison Blues,” which would be his first charting hit. He’d become a decently successful country star in the late ’50s through the mid-’60s, joining barnstorming tours with like-minded performers like Willie Nelson, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and every other big name of the era you can think of.

He charted many singles that you know now, but had some trouble transitioning into an album artist in the mid-’60s. That, coupled with a pill addiction well-chronicled in his biographies and in the biopic Walk The Line, meant that Cash was pretty much down and out by 1966 — an afterthought on Columbia Records, who had another songwriter named Bob Dylan as their big star. He was holed up licking his wounds, wondering if his music career was dried up.

It was Dylan’s producer, Bob Johnston (Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde), who eventually came to Cash’s rescue. By late 1967, Cash had mostly kicked drugs, had been saved by his relationship with June Carter, of the Carter Family, and was ready to mount what would be the first of multiple career comebacks. He hit upon the idea of recording an album at a prison in California; he’d regularly played prisons during his first rise to stardom, and had even inspired another country iconoclast, Merle Haggard, to quit the life of petty crime he’d been leading and become a country singer when Haggard saw Cash perform at San Quentin in the late ’50s. Cash had trouble convincing anyone to let him record the album, as Walk The Line and interviews with everyone in his orbit will tell you, but Johnston signing on made the album a reality.

Oh how history would have been changed, however, if San Quentin — where Cash had performed for prisoners the first time in the ’50s — had responded to Cash’s offer to throw a free concert for its inmates. The administration there responded, eventually, but the bulls at Folsom replied to Cash’s letter first, and he strode into the cafeteria there one morning in January 1968, and changed himself, country music, and the arc of country music history, forever.

“Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.”

The four words that start At Folsom Prison were by way of introduction to the inmates assembled at Folsom, but they ended up being deeper and more impactful than Cash could have known at the time. They served as a re-emergence, after his addiction and commercial decline, his reintroduction to country music. But they also served, in their way, as his intro to the mainstream culture. Cash had little impact on the pop album charts until At Folsom Prison, which would kick off a commercial streak that had him chart multiple albums at the top of Billboard (including one called Hello, I’m Johnny Cash) and get him a variety show that ran for three years on ABC.

After that short, one sentence intro, the album starts, fittingly, with “Folsom Prison Blues.” In its various studio cuts, the pace feels like the jauntily chugging passenger train mentioned in its lyrics; the pace is brisk, but not fast. Here, in front of a gang of hooting and hollering inmates — one of the truths of the album is that their cheers were real, but maybe didn’t occur exactly at the time they are placed on the album — Cash revs his band into a runaway locomotive; this is cow-punk before cow-punk existed, a pointy Lucchese boot pressed to the jugular. Luther Perkins’ guitar solos hit like a one-man riot, a lightning bolt that packs more fireworks into 40 seconds than exist in entire discographies. It’s Cash’s finest vocal performance ever; the way he thumbs his nose and leans into the snarled Reno line invented punk as much as the Stooges did. It’s rare that a musical act’s live peak is so perfectly captured in all its glory, but Cash’s was here.

It’s a testament to the rest of the album that it manages to live up to the standards set by its opening salvo. Split between raucous, hilarious barn-burners and wistful ballads, Cash and the Tennessee Three crafted a set list that managed to speak to and for the prisoners of Folsom, but didn’t aim to proselytize or demean them. It’s an album that manages to humanize prisoners, while also relying on them to give the album a certain je ne sais quoi. Cash wastes no time in endearing himself to the prisoners: At the end of the solemn “Dark as the Dungeon,” during which he cracks up, he lets loose with some cuss words, telling the audience he can’t say words like “hell or shit or anything like that” before telling Johnston, “How’s that grab you, Bob?” He also makes wisecracks about the disgusting drinking water in Folsom, and further endears himself to the inmates when, on the album’s final song, he performs “Greystone Chapel,” a song written for Cash by a Folsom inmate named Glen Sherley.

The songs in between all speak of men in the middle of maniacal sprees of crime and mayhem, the attendant shame and time in the penal system that comes with it, and the lives that they leave in their wake. For sheer mania, it doesn’t get better than the take of “Cocaine Blues,” a T.J. Arnall song that replicates a cocaine binge and the rampage that ensues. Shel Silverstein’s “25 Minutes to Go” has a man on Death Row counting down to his execution, ending with him swinging from the gallows in a bit of black humor, while “Send a Picture of Mother” has a recalcitrant inmate writing a letter home where he simply asks for a pic of his ma. “Flushed From the Bathroom of Your Heart” deals with a breakup by coming up with increasingly blue ways of describing how a lover disposed of you, and “Dirty Old Egg-Sucking Dog” feels like a joke you tell when you’re bored beyond belief and trying to get someone to laugh.

What becomes clear is that Cash might have done the album as a way to jumpstart his career, but the inmates at Folsom were maybe his truest audience. They were the men his best songs were about, men most likely to take some life meaning out of something like “The Long Black Veil.” This was a man preaching to the converted, and he took up their cause as much as they took up his: Cash would record multiple prison albums (1969’s At San Quentin, 1973’s På Österåker, and 1976’s A Concert Behind Prison Walls), and even speak before U.S. legislators about prison conditions and the need for rehabilitation instead of punitive punishments.

Cash played two sets at Folsom, and what you hear on the album is 14 of 16 songs from the first set; the second set’s “Give My Love to Rose” and “I Got Stripes” were the only two songs to make the cut for the LP, since the band burned so brightly during the first. At Folsom Prison ends with that aforementioned Sherley song, “Greystone Chapel,” the story of which could be its own song. Sherley was friendly with the pastor at the prison and secretly recorded a demo tape that he passed onto him. The pastor knew Cash from his previous gigs at Folsom and got the tape into Cash’s hands. Cash loved the song, and then taught it to his band the night before their shows at Folsom. They recorded both of Cash’s sets, and included Sherley’s song as the closer on both; the first time they played it, Sherley himself was in the audience, unaware Cash had even heard his song. He leapt out of his seat and went nuts when he realized Cash was doing his song.

Sherley had been in most of California’s penitentiaries by then, but after the success of At Folsom Prison, he had a short-lived career as a country songwriter and singer himself, writing for Eddy Arnold and joining Cash’s roaming Cash Show in the ’70s (Cash was there at Vacaville when Sherley got paroled). After struggling to cope with life on the outside, Sherley drifted out of Cash’s orbit and died by suicide in 1978 while in hiding, worried about a recent shooting he’d been involved in. Cash had hoped to give Sherley a life outside of prison’s bars, and he did, for a time. Not everyone gets the comeback they deserve.

When it came time to pick the inaugural record for VMP Country, there could be no other album than At Folsom Prison. It’s the urtext of modern country music, the album that set the talking points, ideals, thematic underpinnings, and foundational myths central to the music over these last 53 years. Without At Folsom Prison, you don’t get outlaw country, you don’t get country stars routinely crossing over to mainstream success, you don’t get the Man in Black. Your friend that says “I don’t like country music, except Johnny Cash” has no album to exclude from their stupid genre-biased rule. It’s a rare live album that is perhaps more essential than any of the artist’s albums. It is 46 minutes of pure country perfection, an album that can kick you, cajole you, console you, and make you concerned for a group of people who society tells you you ought to forget.

Johnny Cash walked into Folsom Prison in 1968 to make a comeback, to give his career a jolt, and to get an album out of it. He did all that. But he also made history.

Andrew Winistorfer is Senior Director of Music and Editorial at Vinyl Me, Please, and a writer and editor of their books, 100 Albums You Need in Your Collection and The Best Record Stores in the United States. He’s written Listening Notes for more than 30 VMP releases, co-produced multiple VMP Anthologies, and executive produced the VMP Anthologies The Story of Vanguard, The Story of Willie Nelson, Miles Davis: The Electric Years and The Story of Waylon Jennings. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $36Pages