The Album Where Albert King Paid Homage To The King

Read An Excerpt From The Liner Notes For Our Classics Record For June 2020

“Everybody in Memphis thought that Sam was a peckerwood, just like they were,” Robert Gordon, author of Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, told me in 2019. “If he could do it, why couldn’t they?”

The Sam in question was Sam Phillips, who with his Sun Records seemingly willed a million Memphis record labels into existence with the discovery of the most famous Memphian to ever live: Elvis Aaron Presley. One of the labels started in the wake of Sun Records and Presley was Stax Records, started by a bank teller named Jim Stewart, who loved country music and figured he had enough of an ear to turn his garage into a studio and look for a star. He’d eventually find that in Rufus and Carla Thomas, move his whole operation to a defunct theater on McLemore Avenue — a little over two miles from the Sun Studio storefront where Elvis got signed — in Memphis proper, and launch, with his sister Estelle Axton and the many talented local kids, one of the most important soul labels of all time.

The specter of Elvis didn’t hang over Stax for long — the first golden period at Stax coincided with post-Army, pre-first comeback Elvis — but connections to the King of Rock would pop up occasionally over the years. The first version of “Green Onions” was cut on a lathe at Sun Records the same day it was played on the radio and lit up request lines, becoming an unlikely hit. The Mar-Keys, the first band on Stax Records, used to cover him regularly, and Carla Thomas often talked in interviews about how much she looked up to him over the years. Elvis’ childhood neighbor, Louis Paul, recorded for Stax’s Enterprise imprint after leaving the garage rock legends the Guilloteens (his self-titled debut is a weird amalgamation of southern rock, soul, blues, and country). Elvis himself recorded at Stax Records in 1973, cutting a bevy of songs in the middle of the night — when Isaac Hayes often recorded; he was asked to reschedule — in what amounted to the final serious studio sessions of Presley’s career; the songs would form the bulk of his albums from 1973 through 1975.

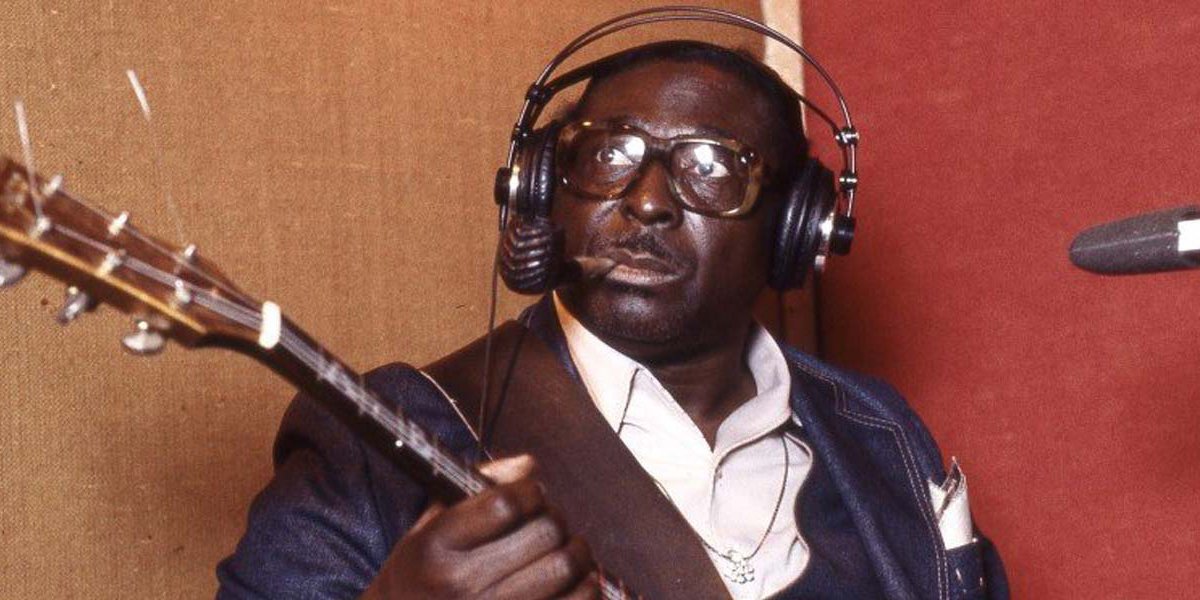

But there’s one artifact that chronicles the cultural exchange between Elvis and the legendary label at 926 E. McLemore Ave. more than any other, a cultural exchange that reimagines Elvis’ blues-indebted rock songs as searing guitar blues of the highest order, the album that brings us here today: Albert King’s King, Does The King’s Things.

While Stax was often pegged as the soul label in the ’60s, it was always more diverse musically than its headline acts suggested. Country was part of the label’s lineup since Stewart started in his garage, and the label released albums of jazz, comedy, gospel, sermons by preachers, and blues in its heyday. That strategy was encouraged by Stewart, but not always willingly across genres, especially where the blues were concerned. Stax had a record store as part of its McLemore Avenue compound, which served as a gateway into the talent of the local kids (like William Bell and Booker T. Jones, among others), and as a way for Axton — who ran the shop — to determine the tastes of the record buying populace. The prevailing wisdom was that the blues were “finished,” that the genre was mostly the province of a small group of hobbyists. But Axton saw differently: the blues records she stocked were still moving, and their audience was bigger than people acknowledged.

Keeping the blues in mind as an avenue for Stax, imagine Estelle’s surprise, in the mid-’60s, to look over at the stacks and see the 6’5” Albert King standing there. Axton acted fast; she basically didn’t let King leave until he agreed to record for the label. She then put the M.G.’s to work figuring out how to make music with him, and wouldn’t leave Stewart alone till he agreed to record King.

It was a career turning point for King, who until that point had been a journeyman guitarist recording for a variety of indie labels like Bobbin and King, and grinding it out on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Born a sharecropper’s son on a cotton plantation, King was known for his size — basically every written account of his life comments how he made his trademark Flying V guitar “look like a fiddle,” even the original liner notes for this album — and for how he played his guitar upside down, backwards, and in a way that guitarists literally spent their lives trying to replicate (Stevie Ray Vaughan got the closest, and according to James Alexander, Bar-Kay and Albert King bassist, Eric Clapton once sent photographers to a show to take pictures of how King was playing to try to crack it). Those distinct, legendary things weren’t enough to sell records early in his career, so his early managers tried to muddy the waters and confuse audiences by saying he was B.B. King’s half brother, which was complicated further by Albert naming his guitar Lucy, in homage to B.B.’s Lucille (namesake of VMP Classics #31).

But the arrival on Stax changed everything: pairing King up with Booker T. and the M.G.’s turned out to be inspired. Among the first 10 songs King cut with the band were iconic songs “Crosscut Saw” and his signature tune, “Born Under A Bad Sign,” written for King by William Bell — who had to whisper song lyrics to King as he recorded in the booth since he couldn’t read them; the line “I can’t read / never learned to write” was true — and Booker T. Jones.

King’s first two LPs — 1967’s Born Under A Bad Sign and 1968’s Live Wire / Blues Power — became standard-bearers for electric blues going forward. In 1969, Stax needed to create an instant catalog after an acrimonious split with distributor Atlantic Records, so they commissioned 28 LPs to be released in a single year. It would later be called the Soul Explosion, but Albert King’s blues were on three of those 28 LPs. The first was his third Stax LP, Years Gone By, and the third was his fifth, a joint LP with Steve Cropper and Pops Staples called Jammed Together that was the closest Stax ever got to having a Guitar Hero album (sidebar: Apparently the entire album was literally jammed together, as Cropper, Staples, and King were never in the same room together during the recording. You’d be hard pressed to find the seams though.) The second King album released during the Soul Explosion was King, Does The King’s Things.

Though it was recorded just months after Years Gone By — which featured Booker T. and the M.G.’s as its band — King’s Things features an entirely different band, owing to Booker T. Jones leaving the go-go-go, record-record-record house band lifestyle for California in the midst of the Soul Explosion. Bar-Kays’ James Alexander (bass) and Willie Hall (drums) form the rhythm section, with Rufus Thomas’ son Marvell helming the keys and the Memphis Horns blowing in the background. M.G.’s bassist Duck Dunn plays some bass as well, and is credited as the arranger and producer with M.G.’s drummer Al Jackson, Jr. And though he’s shouted out in Albert Goldman’s liner notes, Steve Cropper doesn’t play on the album, which makes sense: when you have the Velvet Steamroller working over the six string, you don’t need anyone else.

The selections from Elvis’ songbook that fill out the nine tracks on King’s Things are perhaps predictable. “Jailhouse Rock,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Hound Dog,” and “Heartbreak Hotel” are all here, along with fan favorites like “That’s All Right” and “Don’t Be Cruel.” But what’s unpredictable is how King bends these songs to his will; these aren’t just covers, they’re controlled detonations of the originals. King makes it 2:03 into opening track “Hound Dog” before he can’t contain himself in Elvis’s confines: he takes off on an interstellar solo on his Flying V that, at 2 minutes in length, almost eclipses the runtime of Elvis’ original version of the song by itself. King is in rarefied air, pulling on strings, and bending his guitar note by note, laughing on the track when he knows he’s hit a good lick. It’s like when Michael Jordan would smile and shrug when he dunked. It’s a showstopping moment as the album’s first track, and an incredible filtering of the blues, Tin Pan Alley, rock, and back to blues: Albert got it from Elvis, who got it from Big Mama Thornton, who got it from Leiber & Stoller.

King turns “Heartbreak Hotel” into a solo showcase, too; the song is tripled in length from the original, as King spins out explosive solo after explosive solo between verses, before taking the song out into unexplored vistas, to the point where it’s hardly recognizable as “Heartbreak Hotel” when it reaches its conclusion. “One Night” makes King’s guitar work the literal replacement for Presley; he never sings, and instead his guitar Lucy does the vocals.

For an album centered around Albert King stomping his way through the Elvis songbook with his big frame, maybe the most surprising part is how centered King’s vocals are on the album. His voice was an often underrated part of his act — how could it not be when he could do all he did with a guitar — but the name “Velvet Steamroller” comes not just from his steamrolling guitar, but how his voice could be so soft, it felt like a throw blanket laying on top of you. “Love Me Tender” is as close as King ever got to full-on gospel; his buttery voice sounds like it’s coming from the front of a church, tip-toeing its way around Marvell Thomas’ keys and delivering the song’s middle sermon before handing the reins over to Lucy. His “yeahs” and “uh-huhs” are spritely on “All Shook Up,” and he sounds like he just got done crying before cutting the pleading vocals of “Don’t Be Cruel.”

Like King’s other albums, King, Does The King’s Things didn’t make much of an impact on the charts, but was another album proving he was one of the most exciting bluesmen working in the genre in the late ’60s. He made three more studio LPs for Stax — 1971’s Lovejoy, 1972’s I’ll Play the Blues for You, and 1975’s I Wanna Get Funky — and Does The King’s Things would get a new title when it got reissued by Fantasy Records, which bought Stax in the late-’70s. Blues For Elvis was reissued in 1980, making the title of the album confusing from there on out, especially on streaming services, where it’s called both titles at the same time. It has remained out-of-print on vinyl for these last 40 years, until now.

King might not have been a huge commercial success for Stax like Axton had hoped, but then again, no other bluesman making music then was much of a superstar either. But he’d be the figure most responsible for diversifying the Stax sound outside of the soul that made it famous; sure, some of the label’s jazz artists made fine music, but none of their Stax albums made as big of a mark as King’s did. King would perform regularly until his death in 1992 of a sudden heart attack. He was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013, and his albums remain talismans for new generations of blues lovers trying to learn about the three kings of the blues: B.B., Freddie, and Albert.

It’s not known if Elvis listened to King, Does The King’s Things, but we know he listened to enough Stax to make the studio the home of his last studio recordings. Today, both Sam Phillips and Jim Stewart’s former studios are part of Memphis’ robust music tourism, both turned into museums where you can pay your respects to the men who willed entire music industries out of thin air, all thanks to the talented Kings who recorded for them.

Andrew Winistorfer is Senior Director of Music and Editorial at Vinyl Me, Please, and a writer and editor of their books, 100 Albums You Need in Your Collection and The Best Record Stores in the United States. He’s written Listening Notes for more than 30 VMP releases, co-produced multiple VMP Anthologies, and executive produced the VMP Anthologies The Story of Vanguard, The Story of Willie Nelson, Miles Davis: The Electric Years and The Story of Waylon Jennings. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $36Pages